[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

With a new year beginning, teachers’ thoughts turn to statewide exams. In some courses, math as an example, most questions have but one correct answer. But in other courses, such as reading, history, or English, students need to have knowledge of the three basic kinds of questions so that they can understand what is being asked of them. This knowledge can help them in the classroom, on the ever-present exams, and even in later life. One way to learn about the three basic kinds of questions, which seems to stick with students, is to discuss FACTUAL, INTERPRETIVE, and EVALUATIVE questions as they relate to one little story almost everyone has read, “Little Red Riding Hood.” When I taught seventh and then eighth-graders from the Junior Great Books shared inquiry method, the first thing to do is to have students know which kind of question is being asked. Teachers and parents may need to help with these critical thinking skills.

A FACTUAL question has only one answer. If students have read the story or the piece of literature assigned, they could just place their hands over their mouths and POINT to the ONE answer. Using “Little Red Riding Hood” as an example, pretend the question after the story asks, “What color is the little girl’s hood in the story?” Only one color is correct. It is not purple, mauve, orange, green, blue, or rainbow-colored. The one answer is red. Any student could just point to the answer in the title, but all students agree that only one answer is correct. So, factual questions, as seen on many standardized tests, can only have one correct answer. There is no discussion or disagreement.

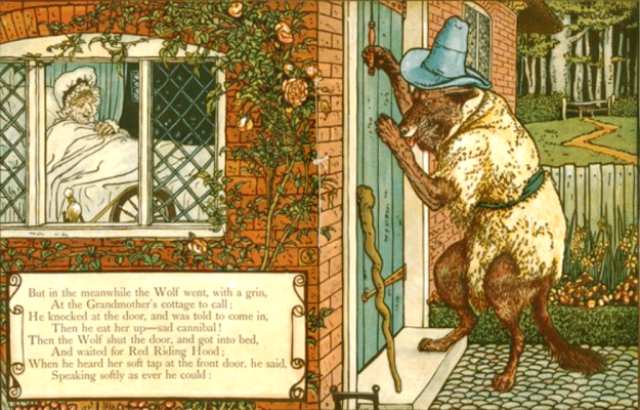

An INTERPRETIVE question about a short story, a poem, or longer piece of literature is a question where there could be more than one correct answer, but the person answering the question must go into the story for proof and explanation about the answer chosen. There is no way a student can just point to the answer. These questions are sometimes dreaded by students, because they KNOW they must prove their answer with evidence. These are the sometimes dreaded discussion questions. Using “Little Red Riding Hood” as the story, an example of an interpretive question is this: “What kind of mother was the little girl’s mother?” Some students may say the mother was very nice and use as evidence that she had baked cookies for her own mother and was teaching her daughter to be a giving and benevolent person. Or they might mention that her clothing in the picture looked well-kept and clean, and therefore she must have been a considerate and neat mother, not a neglectful one. Other students may say she was a particularly bad mother and use as evidence that the mom had sent her young, innocent daughter into the woods known to be roamed by wolves. Or they may mention that the mother SHOULD have gone with the little girl in order to be sure she was protected. But these interpretive questions cannot be answered with just “the mom was good” or “the mom was awful.” Explanations from the story are needed as proof. It’s harder to answer these questions and bluff one’s answer without having read the story assigned.

EVALUATIVE questions are easy to answer, and the answers may come from one’s own experiences. A student can answer an evaluative question without even having read the assigned story. An example is this: “Should parents make their children learn by experience?” Now the students go into their own backgrounds to answer the question. One student might mention that parents do not have to stand their children on a railroad track with a train bearing down at sixty miles per hour to teach the dangers of standing on railroad tracks. After all, there would be no way to use this lesson later if the child were killed…at least not for THAT child. Another student might answer that he was warned to stay off his older brother’s skateboard since he might break an ankle. And then he DID break his ankle when he secretly got onto the skateboard as a toddler. These are fine answers, but they do not relate to the story in any way. In fact, the story does not even have to be mentioned in the answer. Evaluative questions are where some students who have never read the assignment may shine, but that does not mean they learned anything from the reading assignment.

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

In math, most answers are either right or wrong, so one could say that many, if not most, math questions are factual. After all, two plus two equals FOUR, not twelve or nearly four. In history, the date of a certain battle has but one answer. In science, there is one symbol for oxygen, and one alone. But in literature, all three kinds of questions are found, as they are in life itself. When teaching students or one’s own children about answering questions, it is really great to then make them look at today’s news stories or political happenings and ask some factual, interpretive, and evaluative questions. Ask them, “Who won the electoral college vote in 2016?” There is only one answer. This is how critical thinking is ingrained. Be careful of what children watch on television and read online. Much of it comes from people with their own ideas, their own evaluative answers to OUR well-being, and these people’s ideas may not promote critical thinking or our well-being. Discuss what is being put out there as factual. Even many people who are on television as “commentators” and “journalists” might not be as smart as seventh- and eighth-grade students who know about the three kinds of questions.