[spacer height=”20px”]

Waldron was built as a satellite airfield in 1943 for nearby Corpus Christi Naval Air Station. (National Archives Photograph, 1943)

[spacer height=”20px”]

After posting the first article in this series, I received an email message and a 1968 Caller-Times article from Lacey Al Masri regarding Waldron Field. “I was just reading your article on The Paper Trail about Flour Bluff and saw that you are looking for other historic/old stories for Flour Bluff,” wrote Al Masri. “I have an article from the Caller Times, 1968 that is about my grandfather and the prison farm that he ran out in the Bluff. My family has been in the area a long time, before Corpus was even here. My great, great, great, great uncle was James McGloin, the impresario of San Patricio.” I couldn’t imagine it! A farm prison right here in Flour Bluff? This information got my research juices flowing, and I was amazed at what I found. I may have even stumbled upon the real story behind the shape of the 1948 Flour Bluff High School. I will leave it to the readers to set me straight.

The article certainly verified Al Masri’s claim that a farm prison once existed where the kids play baseball, softball, kickball, soccer, and youth football today. This information prompted me to dig a little deeper into the history of Waldron Field. What I found involved multiple uses of the 640-acre plot of land owned by the U.S. Government that is bordered by Waldron Road on the east and Flour Bluff Drive on the west – According to the website Abandoned and Little-Known Airfields, Waldron Field (named for LCDR John C. Waldron* who heroically lost his life in the WWII Battle at Midway) was built as a satellite airfield in 1943 for nearby Corpus Christi Naval Air Station Corpus Christi. By 1947, Waldron Field closed, but it did not stay unoccupied.

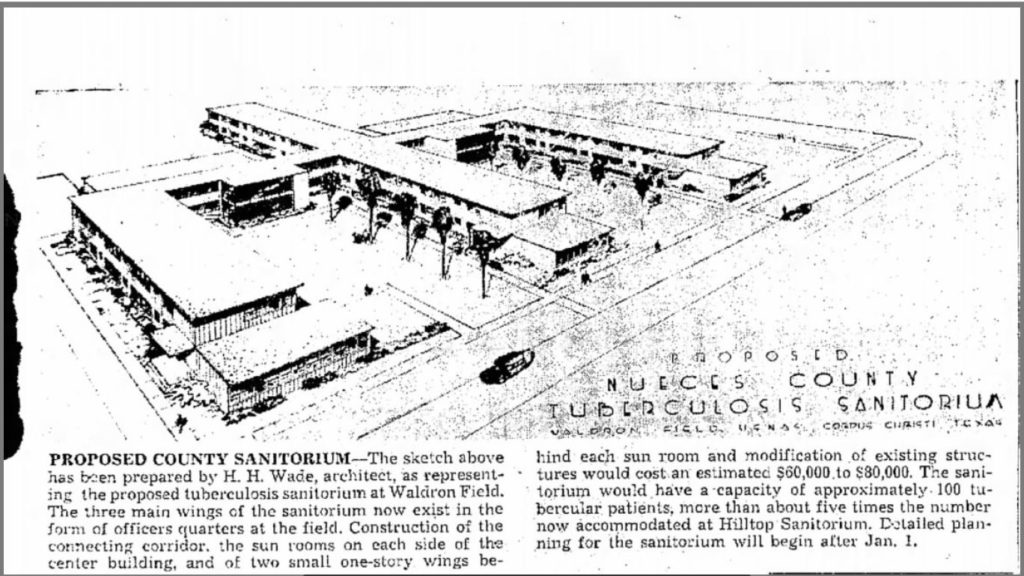

This large tract of land soon drew the attention of the Nueces County Commissioners. John Stallings, reporter for the Caller-Times, reported on December 21, 1947, that County Judge George Prowse was making plans to spend 60 to 80 thousand dollars to convert existing buildings at Waldron Field to expand the Hilltop Sanitorium, where the county could only isolate 21 patients with tuberculosis at a time. The proposed Waldron Field sanitorium would provide rooms for approximately 100 patients. The plans were drawn; then, something happened. Evidently, Judge Prowse’s negotiations with the Navy failed because the hospital never materialized – at least not at Waldron Field. It was eventually built on Highway 9 and opened in 1953. Once again, the Waldron Field property sat unused.

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

Enter Judge Prowse once again. This time, he had a plan for a county prison farm at the Waldron Field location. It was to be operated as a rehabilitation center for prisoners who had committed misdemeanors and was fashioned after a similar farm in Louisville, Kentucky. The property was leased from the Navy for $1 a year. Mr. and Mrs. Dudley Timon (grandparents of Lacey Al Masri mentioned earlier) lived at the farm with their children while Mr. Timon served as the superintendent. Jim Davis, Caller-Times journalist interviewed Timon nearly 20 years after the farm closed, in an article entitled “Prison Farm Superintendent Thinks System Then Was Good,” published March 10, 1968.

In the article, Dudley Timon reminisced about the “good old days” when he served as superintendent of Nueces County’s first and only county work farm from 1947 to 1950. The farm was an attempt to give some persons jailed on misdemeanor charges a chance to do something useful rather than just sit in their cells in the county jail. Timon saw it as a success and told Davis that the inmates usually did not give him much trouble. The article states, “Most of them were not hardened criminals, but rather men who could not hold their liquor or could not keep from writing a bad check every now and then.”

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

Timon was the only guard on the farm. However, when he had to work 40 or so men in separate groups, he sometimes called in “an extra guard or two.” He even used unarmed “trusties.” Another Caller-Times reporter, Hoyt Hager, wrote six months into the start of the program that Judge Prowse saw this use of “trusties” doing maintenance work at Waldron Field as the “guinea pig group” that could develop into a modern prison farm.

Timon told Davis in the 1968 interview, “The prisoners cleaned up the park areas at Padre Island and performed minor road and building repair work. Work a the farm itself included caring for the animals – two milk cows, two horses, 40 goats, and dozens of chickens – and the garden. The men also repaired furniture in a workshop. Timon drew some criticism as farm superintendent because he let some of the men go fishing in the nearby Cayo del Oso. ‘That’s no lie,” Timon said of the fishing charge. ‘We worked Monday through Friday, and if men worked without trouble, they go permission to go fishing.’ He said the fishermen provided fish for the farm’s dinner table and often caught enough to send extras to Hilltop Tuberculosis Hospital and the county jail.”

[spacer height=”20px”]

NOTE: * It should be mentioned that Waldron Field and Waldron Road were indeed named for LCDR John C. Waldron. However, the mascot for Flour Bluff ISD was not named for the USS Hornet, the carrier from which Waldron launched his final mission. The FBISD museum has a school newspaper from 1938 that details how the Hornet was chosen. This pre-dates the construction and commission of the carrier.

Corrections and additional information are welcomed and encouraged. Please send stories to shirley.thornton3@sbcglobal.net.