To preserve the rich history of Flour Bluff, The Paper Trail News, will run historical pieces and personal accounts about the life and times of the people who have inhabited the Encinal Peninsula. Each of the stories comes from interviews held with people who remember what it was like to live and work in Flour Bluff in the old days. You won’t want to miss any of these amazing stories.

[spacer height=”20px”]

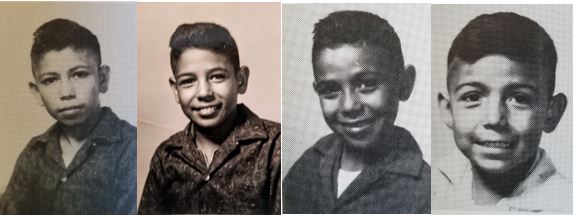

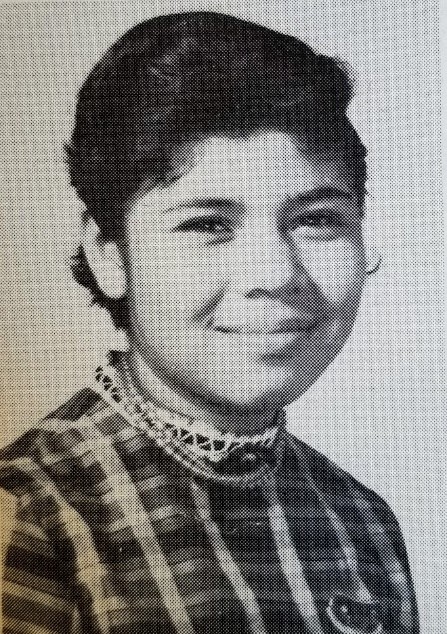

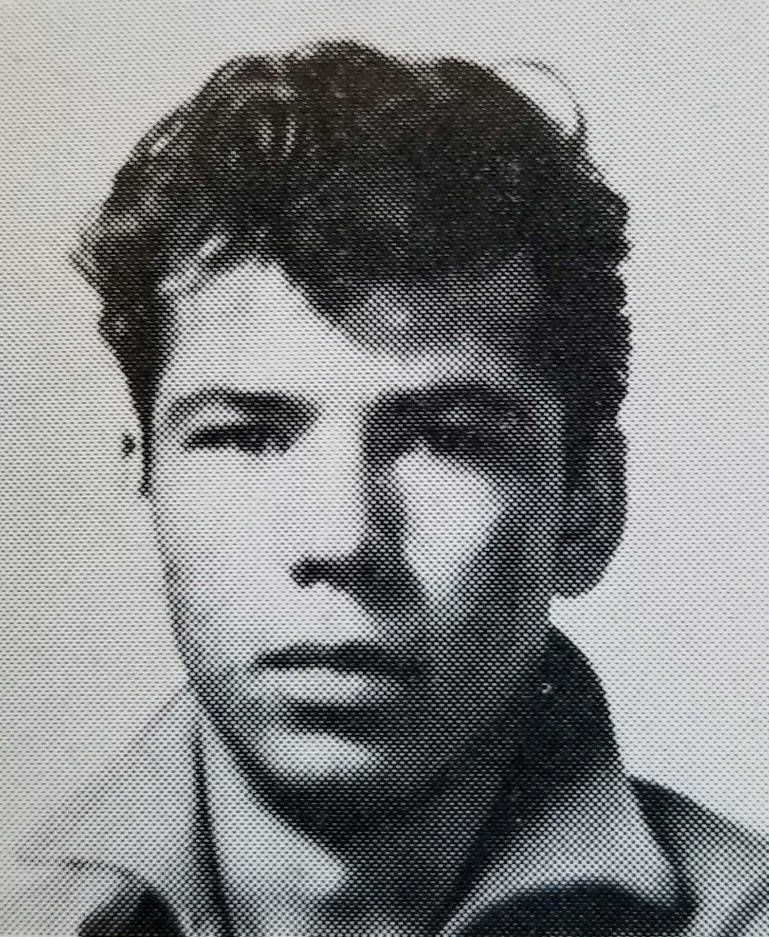

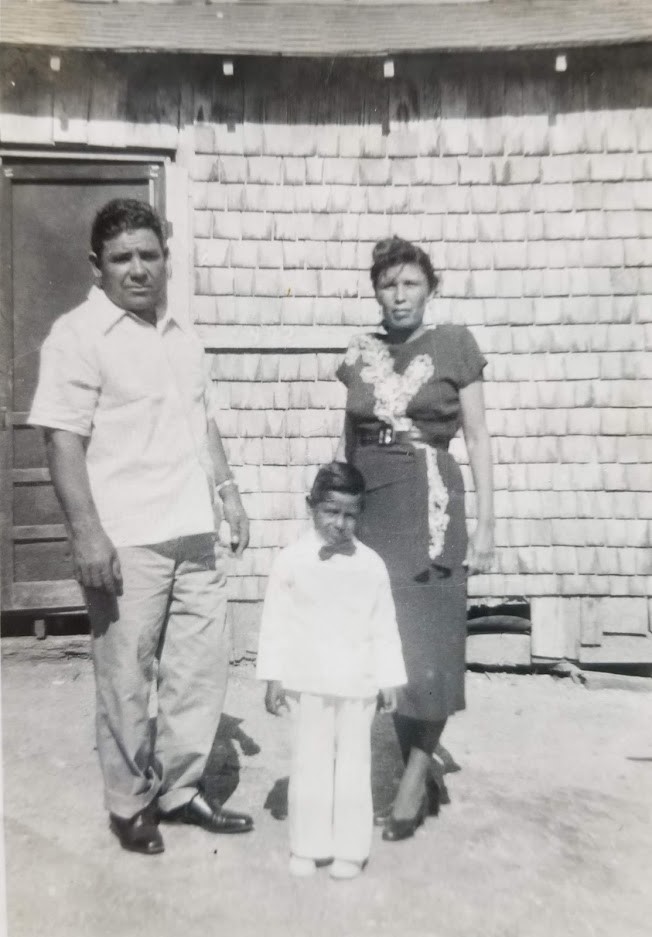

Top row (L to R): Daniel (Dad), Reynaldo (Rey, 4th child), Raul (Rudy, 3rd child), Rogelio (Roy, 5th child) Front row; Bottom row (L to R): Ricardo (Ricky, 7th child), Rafael (Rocky, 1st child), Hortensia (Mom), Rebecca (Becky, 2nd child), and Roberto (Bob, 6th child)

[spacer height=”20px”]

The Torres family was as solid as they come. Both parents worked hard and expected their children to do the same. The family had a “can-do” attitude that got them through even the toughest of times and served each well as they set out on their own. They didn’t let the way things were in Flour Bluff in the fifties and sixties hold them back.

“We didn’t have indoor plumbing until I was a freshman in high school,” said Rey Torres. “We first lived in a duplex on Military Drive that had another migrant family living on the other side. Our dad didn’t think anybody needed school, so it wasn’t a priority for us to go to school. He grew up in the Depression and learned to work at all kinds of jobs that didn’t require a formal education.”

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

“During our formative years, we worked,” said older brother Rudy Torres. “Working is what we did. We traveled from Taft with other migrant workers to Diaz, Arkansas, to pick lots of crops but mostly cotton. Our sister Becky was older, but she never had to work in the fields.”

“One summer in 1950, we took off from Taft in a big cattle truck with a bunch of migrant workers, all sizes and all ages,” said Rey. “We stopped at a place in Texarkana to use the outhouses that were out back. This will never be erased from my mind. I saw a sign that sign that said, ‘N—–s and Mexicans Not Allowed Here.’ We got back in the truck with the illegals. They were illegal because they were not part of the Bracero Program, a program that brought guest workers in from Mexico during WWII. They said they’d take care of that building. One man had defecated in a bucket, and he took the bucket and threw it at the front door. We took off! Of course, we grew through that, got past it, and were stronger for it. Our dad would get us work anywhere to earn money for the family. We had ten in the house we had to take care of.”

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

“Our oldest brother Rocky was born in Taft – as was I, but I was born at home with a midwife. Rocky didn’t start in Flour Bluff Schools until he was 12 or 13. My dad moved us to Flour Bluff in 1954. School had already started. Rocky went to elementary, junior high, and high school in Flour Bluff but left school his sophomore year to join the Marines on January 6, 1961. It took me about three years to learn English at Flour Bluff Schools.”

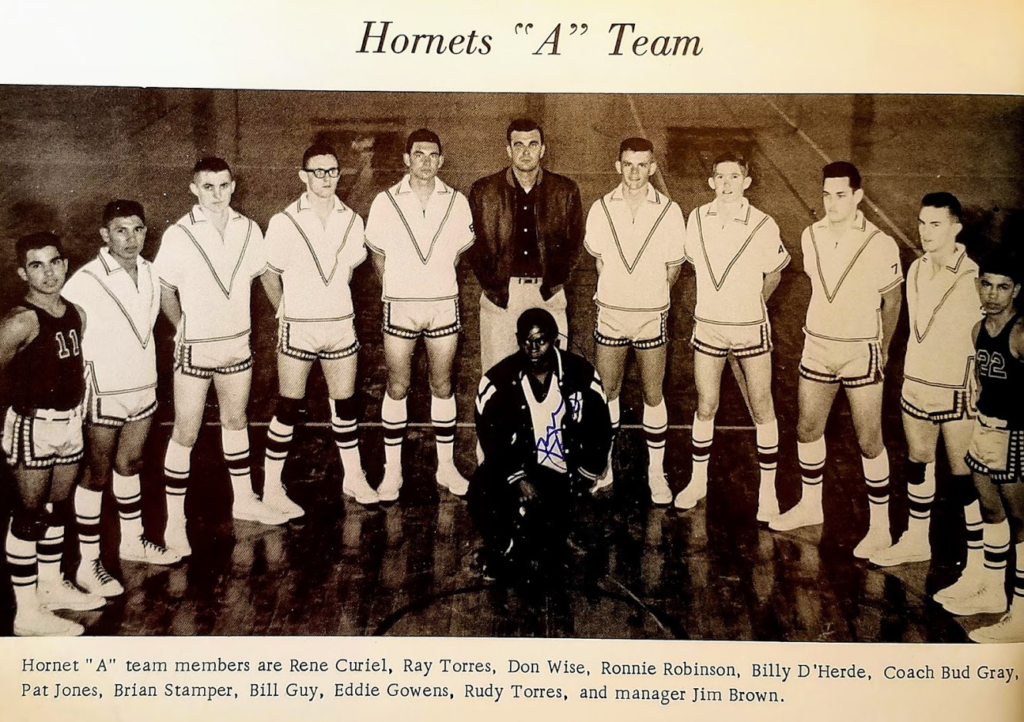

“In 1954, there were very few Hispanic families in Flour Bluff,” added Rudy. “We had the families of Juan Gonzales and Israel Salinas, the Riojas, DeLeon, Curiel, Curry, and Martinez families, and many of them lived in the area west of the stadium.”

“Flour Bluff Schools – like all schools – wouldn’t let Hispanic students in until they had gone to preschool to learn English. I was a product of that, as were many of the other Hispanic kids in Flour Bluff back then,” added Rey.

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

“Because I had to learn English, I was a little older for my grade,” said Rudy. “For some reason, some people looked down on me for that. I was small, and it seemed like I was always fighting for my rights. I tried to accept that I couldn’t be what I wanted to be, but I couldn’t. I had to fight my way out.”

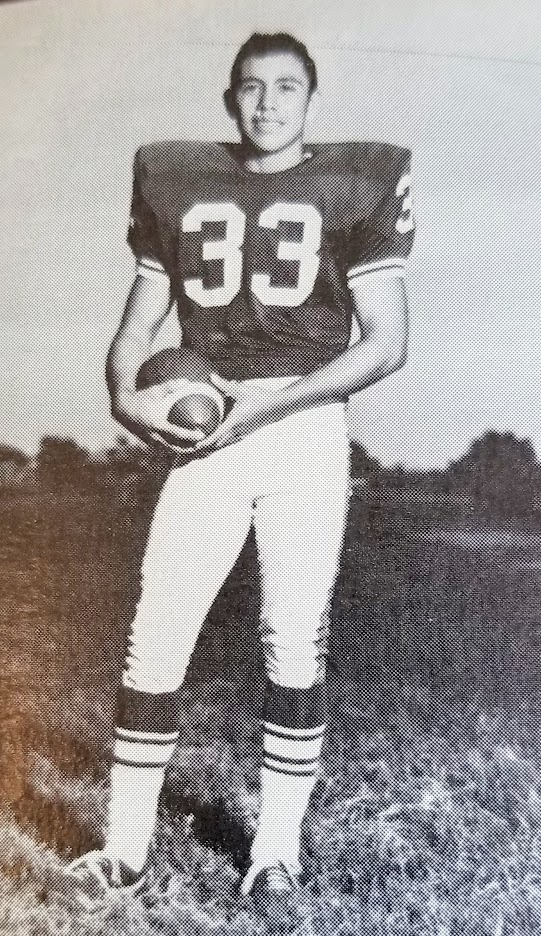

“We all did,” said Rey. “For me, I worked my way up on the football field on Friday nights.”

“When Rey and I were 5 or 6 years old, our Dad took us to La Papa in Mundy, Texas, to harvest potatoes and onions,” said Rudy.

“I went, too,” said Roy. “We stayed in a POW labor camp from World War II that was built for Japanese-Americans. After the war, it was turned into a migrant camp. Half the camp was Mexican Nationals who were part of the Bracero Program, the other half was American migrant workers like us. We picked potatoes from sunup to sundown until Saturday. We only half days on Saturdays, and then everybody got paid. We gave all the money we earned to our mom.”

“The camp had gang showers,” said Roy. “The Bracero women would go first to shower after work on Saturdays. I was about 10, and I and some others had a prurient interest in all that. We slipped up there to see what we could see and met up with a big Hispanic mom who stood guard at the door. She started hollering and ran us off. We had to wait our turn at a distance. After all the women showered, then the men and boys could shower.”

“After we were cleaned up, Mom would give us each a quarter allowance, and we’d go to the little town that was about a mile away to go to the movies,” said Rudy. “We would walk along kicking up the dust, so by the time we got to town we were all dirty again. It was an all-white community, and they would look up and see all these brown people coming into town. The theater was segregated. We had to sit in the balcony. The locals sat on the first level about midway to the screen, mainly because sitting under the balcony meant they’d get hit by the popcorn we threw from the top.”

“I remember one of those Saturdays well,” said Rudy. “We loved getting a cold Coca Cola on ice. One day we came around a corner, and a big bully of a guy sucker punched me and took my Coke away. He knocked the air right out of me. Later, I found the guy and asked him if he remembered taking my coke. Then, I knocked him out.”

“We were free to run on Saturday afternoons and all day Sunday. It was great,” recalls Roy, “until our mother discovered the Catholic convent across the street. That’s when she said we were all going to start attending to church. Oh, how we hated giving up our only day off! The nuns dressed in the long habits. One afternoon after church, the nuns wanted us to play softball. We were pretty athletic, so we agreed. One of the nuns was the pitcher, and I came up to bat. She slow pitched the ball, and I hit it and her, right in the stomach. She dropped to her knees, and all I could think was ‘Don’t tell my mother! Don’t tell my mother!’”

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

All the Torres men can remember times when in their youth when their heritage created problems for them, even in Flour Bluff. Roy told of how he was sweet on a white girl. They’d walk the halls together, and she’d wear his letterman’s jacket. All seemed fine until a coach approached Roy about it and told him that he believed that people should only marry in their own race. He remembers a lot of the schoolteachers feeling that same way.

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

But it wasn’t just race that played a role in the discrimination they sometimes experienced. “I can remember going into town and people asking me where I was from,” said Roy. “I’d tell them I was from Flour Bluff, and they would say things like ‘Flour Bluff? All they have out there are thugs and fishermen.’ I guess they had to put me in one category or the other.”

[spacer height=”20px”]

In the end, it was the Torres work ethic and their ability to use what was at hand to succeed that helped them overcome obstacles and take pride in who they were and what they stood for. Unlike their dad, the Torres boys understand the value of education and used it as a tool to escape poverty. They donned sports uniforms and worked alongside other boys as equals going to battle for their school, something most of the Torres boys would do at a much grander level when they became United States Marines.

______________________________________________________

Be sure to watch for the next story from The Paper Trail News to read stories from other longtime residents of Flour Bluff. Please share these stories. The editor welcomes all corrections or additions to the stories to assist in creating a clearer picture of the past. Please contact the writer at Shirley.thornton3@sbcglobal.net to submit a story idea about the early days of Flour Bluff.