[spacer height=”20px”]

To preserve the rich history of Flour Bluff, The Paper Trail News, will run historical pieces and personal accounts about the life and times of the people who have inhabited the Encinal Peninsula. Each account has been gleaned from interviews held with people who remember what it was like to live and work in Flour Bluff in the old days. You won’t want to miss any of these amazing stories.

[spacer height=”20px”]

Top row (L to R): Daniel (Dad), Reynaldo (Rey, 4th child), Raul (Rudy, 3rd child), Rogelio (Roy, 5th child) Front row; Bottom row (L to R): Ricardo (Ricky, 7th child), Rafael (Rocky, 1st child), Hortensia (Mom), Rebecca (Becky, 2nd child), and Roberto (Bob, 6th child)

[spacer height=”20px”]

Rey Torres was just 20 years old when he was wounded on the front line in Vietnam. What happened that day was the stuff movies are made of.

“We had a gung-ho lieutenant who was from New York,” said Rey. “He wanted to be in the front of everything. We had been going into the valley where we knew there were North Vietnamese and gooks, civilians fighting against us. On three different days, the lieutenant took us in to look for enemy.”

“On the third day, he was leading the whole patrol, and he took our fire team straight in,” Rey said. “If the enemy sees an officer, they’re usually the first to go, so he was fourth in the line. I was third. When we went in, we could smell pot. That’s how we knew the gooks were there. I told the lieutenant that we needed to back off, but he told us to go on in. We followed his order, and they were waiting for us. Everything opened up. The first man got a round through the head. We recovered him. The lieutenant got several rounds to the chest. The lighter he carried in his front pocket was stuck in his chest, but he was still breathing. Another round had hit him in the neck. We opened up and called in for air support.”

“At one point during the ambush, I was left by myself near a banyan tree,” said Rey. “I was able to jump in among the roots of that tree to take cover. It was then that I saw three individuals with grenades. One of them got me. I was hit in the leg and in the back of my head.”

Rey was a man who had lifted many a bag of potatoes and cotton in his youth. It had made him strong, so lifting the lieutenant onto his shoulder to carry him out was something that he could do.

“While I was carrying him, I felt him die,” Rey said somberly. “A guy from Guam was our medic, and he was surprised I could do it. He said he was going to write it up and submit it to the commanding officer because he thought it was something that was deserving of a medal. I didn’t listen to any of that. None of that mattered at the time.”

That never happened because the medic lost his self-control. “When we got ambushed, the medic went berserk. He couldn’t quit crying on the radio when he was calling for air support. I went back and slapped him and told him to call it in. Finally, he calmed down and called in air strikes.”

[spacer height=”20px”]

Rey’s older brother, Rudy Torres, created this display to honor his brother’s bravery in battle. (Courtesy Rudy Torres)

[spacer height=”20px”]

It was just one of many incidents Rey was involved in while on the front lines, but this one earned him a Purple Heart and landed him in the hospital in Guam. The doctor who saw him there made arrangements to have him sent to NAS Corpus Christi for surgery and hospitalization, which allowed him to be near his family and to receive special care. The commander of the base at that time was a man named Blackmon, father of Steve Blackmon, one of Rey’s Hornet basketball teammates. A surgeon from Walter Reed Hospital was called in to work on Rey.

[spacer height=”20px”]

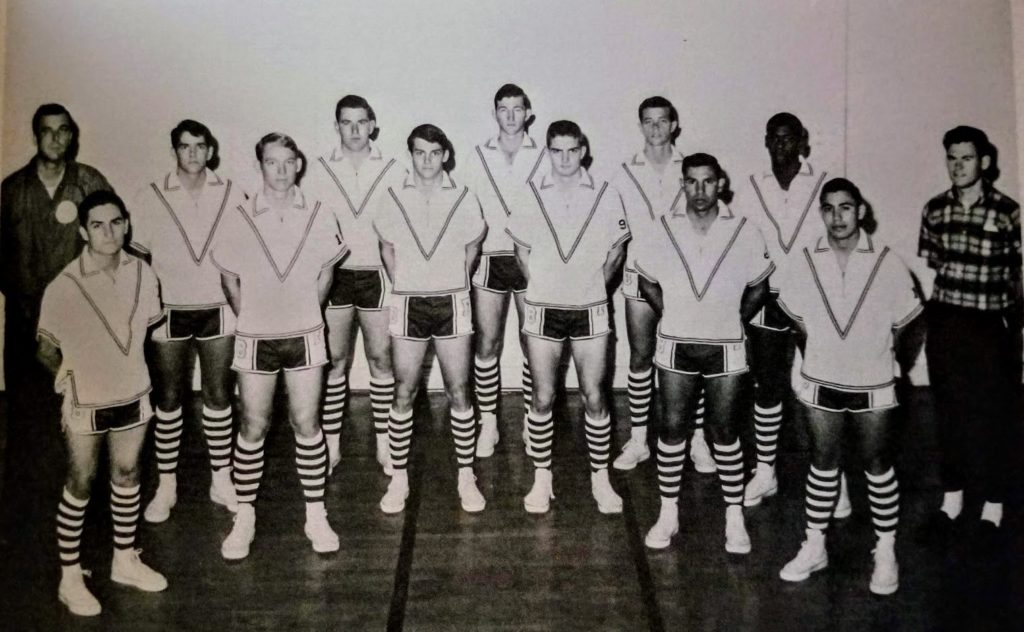

(L to R) Coach Bud Grey, Bobby Ronje, George Barnes, Donny D’herde, Emmett Weyand, Steve Blackmon, Tosser See, Jimmy Gowens, James Bowman, Rey Torres, Gilbert Walker, Roy Torres, Mgr. Ernest Morris (1966 Hornet Yearbook photo)

[spacer height=”20px”]

“Commander Blackmon really gave me special treatment,” Rey said, “and I really appreciated it.”

Rudy Torres, Rey’s older brother and fellow Marine, added, “He had a cast on both legs up to his hips. He was wounded in the same leg that he had had two football injuries. He spent several months in the hospital, and they told him that he would never be able to walk again.”

But Rey did walk again. In total, he spent 13 months in the U. S. Marine Corps, much of that recuperating from his injuries in battle. Once out of the Marines, he made good use of the GI Bill to get his college education. Instead of making history and playing sports, Rey would find himself teaching history and coaching sports.

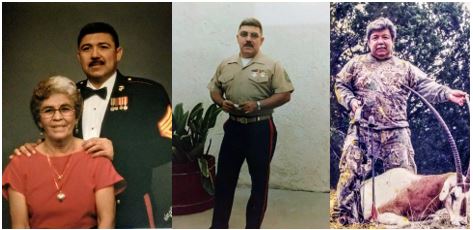

Bob Torres with mom, Hortensia, in his Marine’s uniform, and at the end of a successful hunt (Photos courtesy of Rudy Torres)

[spacer height=”20px”]

Bob Torres graduated Flour Bluff in 1970, which made his mother immensely proud, and he started his college career at Texas A & I in Kingsville as an oceanography major. Though he would eventually receive a B.S. degree from the University of the Incarnate Word, his life took a turn that led him to enlist in the U.S. Marine Corps like his brothers before him. Before taking his leave, he donated a 100-gallon aquarium to the Flour Bluff High School.

When Bob was recruited to the Marines by his brother Rudy, it made his mother cry. “Mother didn’t like it – that we chose the Marine Corps,” wrote Bob in a eulogy he wrote for his mother. “I’ll never forget that. But when I’d made that decision and left the house, she was proud of me, too.”

“I was trying to get Bob ready for the Marine test, and he was busy with his girlfriend,” said Rudy. “I was worried that he wouldn’t do well because he wasn’t studying.”

When the test results came back, Bob had scored very well. Rudy wanted to make sure his little brother went into a field that would teach him a vocation, but Bob had other plans. He wanted to go into reconnaissance. Bob was sent to Okinawa, where he met up with his brothers, Rocky and Rudy. It was here that he started writing sports stories in his free time and taking pictures. He became a freelance photojournalist. This got the attention of the editor of Stars and Stripes published some of Bob’s stories. He displayed a real talent in the area, so he made a lateral movement from the administrative field to public affairs.

In 1973, Bob was sent to San Diego, California, where he continued his work in journalism. He was given the job as editor of The Chevron, a weekly publication of Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego. Then, Bob worked as an OSO, Officer Selection Officer who recruited Marines to become officers. By 1974, the Vietnam War came to an end. Bob was in Albany, New York, which was not a good fit for him. Brother Rudy made some calls, and Bob received a Public Affairs position in San Antonio, Texas, in 1977.

“Bob was following in the footsteps of two really good public affairs officers, but Bob was exceptional,” said Rudy. “He just set the world on fire. He made Staff Sergeant after only six years in the Marine Corps, which is very unusual.”

Bob served for 22 years, a far cry from his initial intent of spending only two years in the Marines. In addition to California, Okinawa, New York, and San Antonio, Bob served in Washington, D.C., Hawaii, Iwo Jima, Korea, and the Pacific Islands before winding up at NAS Corpus Christi as the Public Affairs Officer. It was there he wrote for Wingspan. Bob retired a Gunnery Sergeant in 1994. He went on to work for Peterson Publishing Company, where he wrote articles for Bow and Arrow Hunting and Lone Star Bowhunting magazines. Bob’s job introduced him to Marine Corps Lt. Col. Oliver North, Congressional Medal of Honor recipient Bob O’Malley, singer Ted Nugent, actress Geena Davis, high ranking officers in all branches of service, and many other people of note, including screenwriters in Hollywood. He was even allowed to hunt a black buck in Hawaii and write about it for Peterson. Bob often wrote for Marie Speer’s paper, The Flour Bluff Sun.

Bob never went to war while in the Marines. He did, however, do battle against diabetes. He suffered multiple strokes and eventually passed away on September 10, 2014, in Corpus Christi, with his Marine brothers, Rudy and Rey by his side. Because Bob Torres was a writer, he leaves behind a legacy in the stories he told.

(Left) Virgil Selph and Rebecca Torres on their wedding day (Right) Virgil Selph in dress blues, June 1960 (Photos courtesy of Virgil Selph)

[spacer height=”20px”]

Rebecca Torres, sister to the six Torres boys and second in the birth order, did the next best thing to becoming a Marine; she married one. Becky attended Flour Bluff schools and after graduation became a Licensed Vocational Nurse before meeting and marrying a Marine, Virgil Thomas Selph, in 1965. By then, Virgil had been in the Marines almost five years, having served in North Carolina, South Carolina, Okinawa, and Albany, Georgia. He was a corporal when he was stationed at Corpus Christi Marine Barracks Supply Field, and Becky was working as an LVN for Dr. Hughes in Flour Bluff when the two met.

“Our daddy had a shotgun for everybody who wanted to date our sister,” said Rudy. “He was driving everybody away, but Virgil somehow earned my dad’s approval.”

“Virgil was from Fitzgerald, Georgia,” said Rey. “When he graduated high school, he was offered sports scholarships to places like Georgia State, Georgia Tech. He held state records all four years of high school in track. He gave Becky a couple of bracelets full of state medals. He had huge calves.”

“He was kind of slim, but he had built up his calves from running in the countryside to deliver newspapers at 4:00 in the morning,” added Rudy.

“Virgil grew up very poor and was anxious to be out on his own,” said Rey. “He chose the Marines over college. I knew him when I was working at the base during high school. I remember these Navy guys giving me a lot of trouble, and I couldn’t defend myself. Virgil, who wasn’t my brother-in-law yet, came to my rescue and let them know if they mistreated me that they would have to answer to him. I just stood there thinking ‘Virgil’s a man.’”

Virgil was serious about Becky. He even converted to Catholicism and went through the classes. Rudy served as his godfather in the process, and Virgil eventually was able to marry the love of his life. Soon, Virgil was deployed to Da Nang, Vietnam, and Becky gave birth to Michael, their first child, just after he left.

After his return from overseas, the Selph family traveled wherever the military took them, including California, Okinawa, South Carolina, with two additions, Mark and Michelle. When Virgil retired in 1981 as a Master Sergeant, Becky wanted to go home, so they returned to Flour Bluff. That was January 1981. They raised their children, and Becky became a master at making quilts. Becky passed away February 24, 2007, after succumbing to cancer. Virgil still lives in Flour Bluff in the home that he and Becky called home, and though he’s in his eighties, he mows his own yard and takes care of himself.

“Virgil still loves our sister very much,” said Rudy. “His house has so many pictures of her. We have always been so proud to know him. He is courteous and honorable and completely devoted to our sister’s memory and his children.”

The Torres men and their brother-in-law Virgil Selph gave of themselves to preserve the freedoms of this country, as did many others who served in all branches of the service. May we never forget the sacrifices made by them and their families. May God bless all who are still with us.

_________________________________________

The editor welcomes all corrections or additions to the stories to assist in creating a clearer picture of the past. Please contact the editor at Shirley.thornton3@sbcglobal.net to clarify or submit a story about the early days of Flour Bluff.