[spacer height=”20px”]

The stories of Corpus Christi battling its streets problems reminds me of another story…

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

A man who was passing through Chicago discovered another man buried to his neck in mud. “Sir, it appears you have a problem. You must need some help,” the passerby said.“No, thank you, I’ll be all right. I have a fine horse beneath me,” the man in the mud replied.

People have proven many times over that while under the influence of necessity and behind the power of many, a whole can be greater than the sum of its parts. As the old adage goes, “Together, we can move mountains.” A brief look to history shows us how Chicagoans demonstrated the truth of this idea during the mid-19th century. Only they weren’t moving mountains; they were moving the entire city!

At the time, Chicago was young – a mere 20 years – and it had a severe drainage problem. Streets became impassable in wet weather. Chicago is situated along the southwestern edge of Lake Michigan – a body of water the size of a small ocean. The elevation at the time was essentially no different than that of sea-level. Besides being an annoying living condition, health and sanitation issues quickly became a major concern. The people needed an answer if they hoped to see their city grow and reach a point in which it could eventually become home to nearly 3 million people and one of the tallest skyscrapers the world has ever seen.

After several failed attempts to plank over the streets and redirect standing water into the river, the Chicago Common Council (i.e. City Council), behind the plans of E.S. Chesbrough, determined that the only hope was to manually elevate the city (anywhere from 4-14 feet, location pending) and install the country’s first comprehensive storm-sewage system to solve the drainage quagmire and ensure the city would not become a permanent cesspool and breeding ground for cholera.

A solution of such extreme measures, however, stimulated a greater and far more interesting obstacle: How in the world would they lift a city full of large buildings, homes, hotels, and not to mention – people – 14 feet in the air? Enter George Pullman. Pullman developed a method employing hundreds of men turning thousands of jack screws beneath building foundations. Over the course of two decades, they jacked buildings up like cars (many with people still inside them) so that new foundations could be successfully poured beneath them, leaving both the city and its structures permanently elevated. Smaller homes and businesses were placed on rolling devices and wheeled to new locations. The streets were then leveled up to new heights to meet the level of front doors. New sewage drains were installed and designed to run from the streets down to the river and lake in an amazing effort which lifted Chicago from a wasteland of sludge.

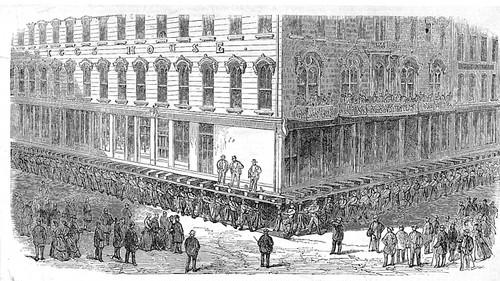

A report by the Chicago Press & Tribune in the March of 1860 issue:

“The entire front of first-class buildings on the north side of Lake Street between La Salle and Clark streets is now rising to grade at the rate of about twelve inches per day. It will be at its full height by tomorrow night, when it will constitute a spectacle not many of our citizens may see again, if ever, a business block covering nearly one acre, and weighing over twenty-five thousand tons resting on six thousand screws, upon which it has made an upward journey of four feet and ten inches.”

The task of raising the Briggs House, a hotel at Randolph and Wells Streets, in 1857 involved the coordinated efforts of hundreds of workers. During the raising, the hotel remained open for business. (Chicago Historical Society)

[spacer height=”20px”]

Cities, they say, develop a persona of their own, all of which is nothing if not indicative of the spirit of its citizens. Ultimately, when problems arise, people become faced with choices: accept your collective fate, ignore the coming future, or act accordingly. Mid-19th century Chicagoans proved early that they were determined to create the possibility that their city might eventually become the megalopolis that it is today. Little did they know that shortly after they were able to ascend from the squalor of sewage, the citizens of Chicago would be faced with yet another test in 1871, The Great Chicago Fire. This time they would be forced to ascend from the ashes. Ultimately, the people, like their story, now belong to the ages. But, such as any good anecdote – if remembered and studied – it can offer deeper answers for particularly troubling problems of the present. Perhaps Henry Ford said it best: “Coming together is a beginning. Keeping together is progress. Working together is success.”

[spacer height=”20px”]

Articles about Corpus Christi streets:

Takin’ It to the Streets: A Highly Qualified Committee

Takin’ It to the Streets: A Man with Questions

Takin’ It to the Streets: Addressing the Status Quo