[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

Lacy Lee Smith recalls how he got his unique first name. “My mama was going to name me Travis, but she had a friend who had just had a baby and had named him Travis. So, she named me Lacy, after an uncle, I think.” Birth records for the United States indicate that only 5,154 boys have been named Lacy since 1880. Like his name, Lacy Smith is a rarity.

Lacy’s mother, Rady Elizabeth (Jones) Smith, was born on September 11, 1909, in Marquez, Texas. His father, Rupert Allen Smith, was born on May 11, 1889, In Belton, Texas. Rady and Rupert, married on January 16, 1923, had five children: Ruby Fay in 1925, Joseph Allen in 1927, Johnny Wesley Neal in 1929, Lacy Lee Smith in 1932, and David Kent Smith in 1934. Their marriage ended in divorce, which is part of the reason for Lacy finding his way to Flour Bluff in 1936, shortly after the oil and gas boom in the area. During the Great Depression, the family fished and even worked as migrant farm workers.

“We’d travel West Texas to pick cotton and down to the valley to pick onions and potatoes. In those days, you could only sell a perfect onion or potato. We would pick black-eyed peas, too, and we lived on the culls that were left in the fields. Whatever there was to do, that’s what we’d do,” said Lacy. “Sometimes we’d pick crab meat. We’d walk along the beach in Port Isabel and dip up crabs with a net. Then, we’d build a fire and boil them and get the meat. We got a dollar a pound for crab meat because it was handpicked.”

Lacy tells of a different Flour Bluff than the one everyone knows today. “When we first moved to Flour Bluff, none of the roads were paved. They didn’t even have oyster shell on them; they were just dirt,” he recalls. “There were a few cars, mostly Model A’s, with some Chevrolets and Chryslers. We had a 1938 Ford pickup.”

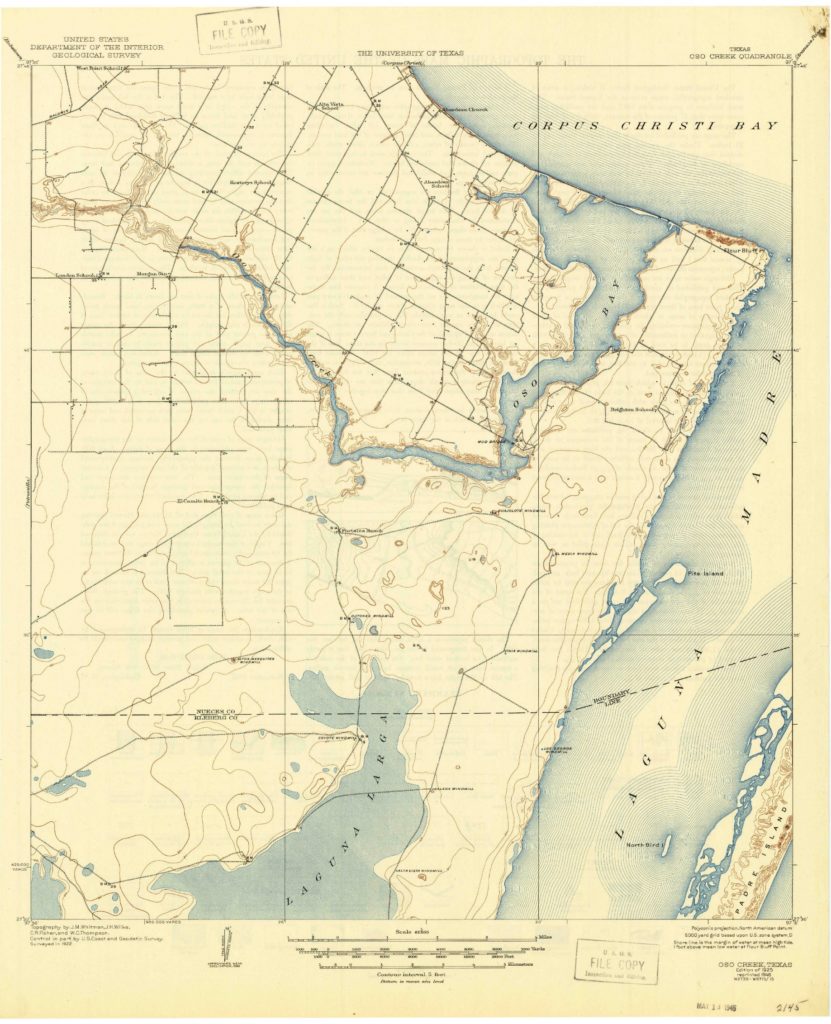

At the time that, Lacy said the main way into Flour Bluff was across Ward Island. “We drove across Ward Island on an oyster shell road that went on down toward Dimmit’s Island. There were a couple of bridges on that road. Mud Bridge was out on what became Yorktown Boulevard, which didn’t go all the way to the Laguna Madre then. There were very few roads in Flour Bluff,” Lacy explained. “It wasn’t until nearly 1940 that they upgraded the roads with oyster shell. Later, they brought in caliche and gravel from Mathis. That was because of Humble Oil and then the base.”

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

In the 1930s, Lacy said there was very little going on in Flour Bluff other than fishing and drilling. “In about 1938 or 1939, one of the wells blew out in the Laguna Madre and caught fire, and you could read a newspaper on our front porch at 12:00 midnight because it burned so bright. It burned for about a year and left a big crater out near the Humble Channel that you can still see today about 100 yards south of the causeway. I don’t think anyone really knows how deep it is,” Lacy said. “The derrick and three boxcars are down in that hole. They were doing everything they could to plug it, and they finally drilled another well next to it and plugged it with drilling mud to cut it off.”

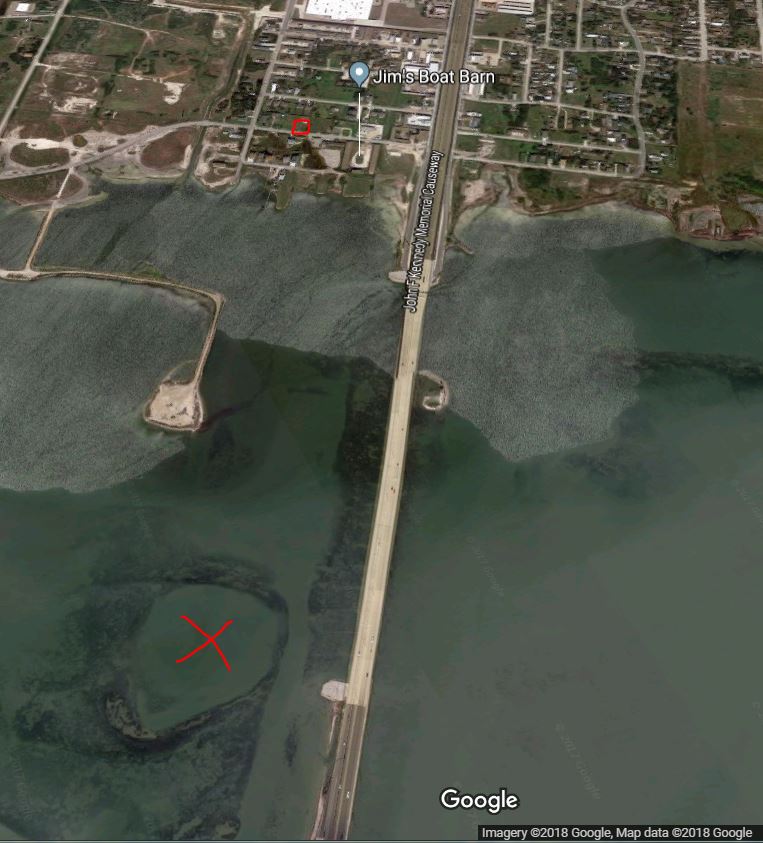

At that time, Lacy’s family lived on what would become Laguna Shores Road across from the first Flour Bluff Volunteer Fire Department. The house was torn down about two years ago. (See map below. Lacy’s house is marked with a red square and the crater with an X.) “The first road we called Laguna Shores was just a dirt road running along the shoreline, which was about 200 yards farther out in the water. When they started sinking those oil and gas wells, the whole shoreline just sunk.”

Note the two red x’s. The one at the top is where Lacy’s house sat. The one at the bottom marks the crater left by the blowout of the well. (Source: Google Earth)

Lacy talked about how the people lived in Flour Bluff and along the Laguna Madre in those days. He reiterated what he told Nathan Wilkey in a 1988 interview. “Most people in Flour Bluff had wells or collected rain for water. Fresh water was not as much in demand or wasted back then. There was no indoor plumbing, no refrigeration, no ice. We only took a bath maybe once in the winter.”

When it came to handling sewage, he told Wilkey, “You had a wooden privy sitting over a hole you would dig, and when the hole would fill, you would dig a new hole and move the outhouse. This was also the case at the school house.”

Lacy said that some families, like the Dunns and the Roschers, ran cattle in those days. “It was open range back then, and the cattle would just run wild and free,” Lacy said. “The Johnsons raised a few horses, and Tom Graham raised hogs. He had a contract with the government to pick up garbage at the base to feed his hogs. A lot of them escaped into the wilderness and ran wild. There was a lot of brush back then for them to live in.”

“Burton Dunn grazed his cattle mostly on the island and ran them straight across the Laguna Madre to Flour Bluff where there were holding pens,” said Lacy. “It was about where Yorktown and Laguna Shores meet today. Back then, the Laguna Madre was shallow all the way across. The commercial fishermen couldn’t even get a load of fish to the dock without unloading their catch into smaller loads,” he told Wilkey. “One day a storm blew in, the same day Jigs Danley died of a heart attack down in Baffin Bay, and the cowboys were driving the cattle across the water. Lightning struck and blinded the cattle, making them move into the water where they couldn’t get out. I called Dunn, and he hired me to get them out with my boat and barge and take them back to Padre Island and turn them loose. He still owes me a calf for saving those cattle,” Lacy said with a laugh. “I don’t have ill feelings about it; he paid me well.”

Lacy’s memories of his days at Flour Bluff School are not nearly as numerous as his memories of fishing. “I walked to school in Loyola Beach, but when I came to Flour Bluff I took the bus. The bus driver’s name was Hoot Johnson. He picked up all the kids and took us to school,” he said. In 1937, a new brick building was constructed at the Waldron Road and Purdue Street intersection with the economic backing of Humble Oil. All children on the Encinal Peninsula attended the same school by then. “Our superintendent was Sherm Hawley, and he used to chase us with a car when we played hooky.”

[spacer height=”20px”]

Flour Bluff School, ca. 1937 (Photo courtesy of Flour Bluff ISD)

[spacer height=”20px”]

Later, Hawley would become the justice of the peace. “He also owned a drug store right outside the base,” recalled Lacy. “I remember that a plane off the base crashed right next to it,” something that several other Flour Bluff residents can recall. “There were planes crashing everywhere around here back then. Two crashed into each other just at the end of what is now Hustlin’ Hornet Drive. They never recovered any bodies,” he said.

“When I was just a big teenager, I befriended a bunch of sailors who were on duty at Waldron Field. We’d target shoot with their .45s, and they’d let me drive their jeeps,” laughed Lacy.

Still most of Lacy’s life was centered around fishing. In 1951, he married his first wife, Carol Ann Suggs. “I was working vacation relief with Humble Oil then, but I got laid off. They wanted me to go back to work for them the next year, but by then I had started fishing full time. Fishing is in my blood,” said Lacy. Lilia, Lacy’s current wife, asked if I could guess Lacy’s astrological sign. “Pisces,” he said laughing.

“Most of my life I did illegal fishing for drum, red fish, or trout. I knew the bay by night by the stars. People didn’t think I had a job because I was always working at night. I could leave here and go anywhere in that bay that I wanted to by dead reckoning. I’d put my nets out and hide them under the water. Then, I’d go back and get the fish out of them. I could go by the beach, the stars, the depth of the water, the sound of the bottom – whether it was shell or mud – to find my way by night.”

Lacy named some of the other commercial fishermen in the area. “There were Vannoys and a lot of them! Fred Corkill, Little Jimmy Johnson and big Jim Johnson, the Bartas, Bobbie Kimbrell, and Rudy Jeletich. The first time I met the Jelethiches was in 1936. They had a flat-bottomed boat and a bunch of Coleman lanterns. They’d walk across the bayfront out there where the base is now and dip up crabs at night. One night they brought in 1000 pounds of crabs. I didn’t go with them, but I saw the catch that they brought in.”

A resounding “No!” was the answer to the question regarding the commercial fisherman’s role in depleting the waters of fish. “It was the environment.” Staying true to every word he shared in the 1988 Wilkey interview, Lacy explained that both geological and habitat changes played the biggest role. He said that drum and sheepshead used to be the dominant fish in the Laguna, but over time, the red fish and trout took over. He spoke of how the bottom used to be sand where coquina shells dwelt; this was the food supply for the drum and sheepshead, where it was 90% sand and mud, but with time and man-made changes like the 1950 construction of the JFK Causeway, it became 90% grass, mud, and algae.

“This cut off the food supply for the drum,” he said. Even though the Intracoastal helped the fish in the Laguna Madre, the causeway cut off the flow of fresh sea water from the north. There were only two bridges, the one over the Intracoastal and the one over Humble Channel.”

“It changed fishing and the fishermen. Some fishermen, like Ace Kimbrell and Earl Rush, opened bait stands for the tourists,” recalls Lacy.

“During the 1930s, the salt content got so bad that the fish were incoherent. You could walk along the shore and gig them with pitchforks. The market value was ½ cent per pound. The big change came when hurricane Carla blew through, and you started to see seagrass growing,” he told Wilkey. He even said that the salt content got so high that the fish went blind and eventually died. “Then lots of rain started to fall, filling up the creeks that flow into Baffin Bay. The salinity level dropped, and the water was good for the fish again. There’s an article in the Kingsville Times about me and my brother going out into the bay to catch fish in 1939, the first ones after the fish came back.”

Marine biologist Ernest Simmons published a report on July 29, 1959, that echoes what Lacy knew to be the causes for the decline in the fish population. Lacy also spoke of how the freezes of 1952, 1962, and 1983 killed most of the fish in the inland bays. “But, the fish replenish themselves in about two years,” he said.

When asked about something unusual that he saw while fishing, he said, “I guess one of the strangest things I’ve seen was a big leatherback turtle. I was crossing Matagorda Bay in a shrimp boat and saw its head sticking up, and I thought it was a man in the middle of the bay. When I got closer, I could see that its head was bigger than a man’s!”

Leatherback turtle (Photo credit: WikiCommons)

“After one of the big freezes, Morris Vannoy caught a leatherback turtle that was six feet long. He killed it, and everybody down there had turtle meat. The shell was lying in the yard. I could lie down in it like a boat it was so big. I was friends with Morris’s son, Sidney. He became a preacher like Morris. Sidney built boats for me, and at times we’d fish together.”

Lacy knows the dangers of commercial fishing. He talked of losing a cousin, J. W. Grimes, in Baffin Bay and an aunt who just disappeared from the fishing boat one day while her husband was catching bait with a cast net. “When he came back up, she was just gone. There never was a trace of her.”

Sadly, his only son, Allen Kent Smith, along with Marty Pritchard, died November 29, 1976, while running gill nets at night, outlaw fishing, in the Laguna Madre. “They overloaded the boat, and it sank. Kent swam ashore, but he died from hypothermia. He was in knee-deep water when he died. He was going out in a 24-foot boat, and I started to tell him to use my bigger boat, but we started talking about something else. If he had used my boat, he wouldn’t have drowned. He’d have made it.”

[spacer height=”20px”]

Headstone located at Duncan Cemetery in Flour Bluff

[spacer height=”20px”]

Lacy ended the interview talking about his best year for fishing. “It was ’07,” he said. “Ruth West bought a million three-hundred thousand pounds of drum. ’08 was the last year I fished.” It was that year that Lacy had a stroke and suffered other physical ailments. I asked him if he thought he’d still be fishing at 85 if he hadn’t had his illnesses, and he said without hesitation, “Oh, yeah. Every day!”

NOTE: The editor welcomes all corrections or additions to the stories to assist in creating a clearer picture of the past. Please contact the editor at shirley.thornton3@sbcglobal.net to submit a story about the early days of Flour Bluff.