As Flour Bluff School ends its 128th year of educating children, it only seems appropriate to revisit the story of a man, George Hugo Ritter, who settled the Encinal Peninsula and started the school for the children who moved into the area in the 1890’s with their families. Many of this man’s descendants have remained in the area, some still teaching in the school. Recently, the Flour Bluff I.S.D. Board of Trustees named a road in honor of this pioneer and his family. The dedication of Ritter Road was postponed due to the Covid-19 restrictions. School officials plan to hold the dedication ceremony as soon as the restrictions are lifted.

[spacer height=”20px”]

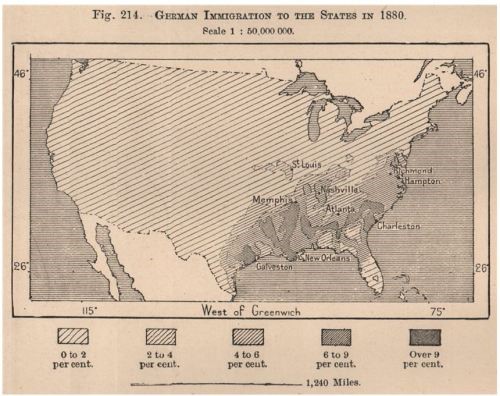

“The Universal Geography”; by Élisée Reclus, edited by A.H. Keane, Published by J.S. Virtue & Co., London [USA], printed 1885

In 1871, after a series of wars, Prussian prime minister Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898) brought about the union of the German states (with the exception of Austria) into the Second Empire, or Reich. Germany quickly became the strongest military, industrial, and economic power in Europe. While Bismarck governed, an elaborate system of alliances (unions among groups for a special purpose) with other European powers was created. Because of the political changes, between 1871 and 1885 a million and a half Germans emigrated overseas–nearly 3 1/2 percent of the population. Of those whose destination was known, 95 percent went to the United States. George Hugo Ritter, the man who would be the first to settle Flour Bluff, was one of those immigrants.

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

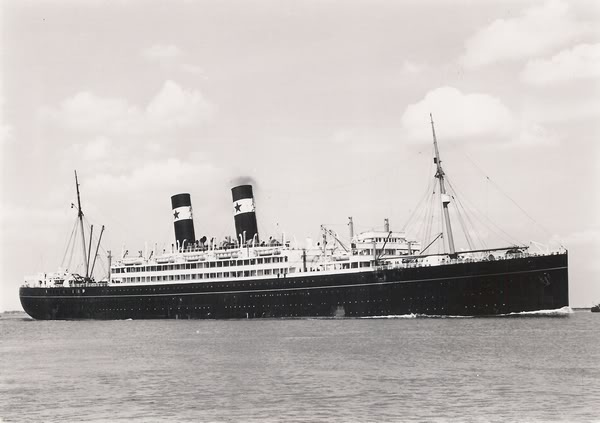

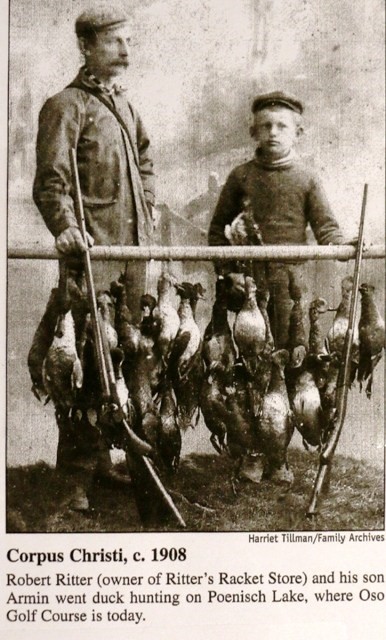

Born in Germany in 1866, George Hugo, who went by his middle name, left his native country to avoid conscription. This nineteen-year-old, blue-eyed “Prussian” arrived in New York aboard the SS Pennland in 1885 and entered the United States through Ellis Island. After spending an unknown amount of time in New York, Hugo eventually booked passage on a steamer to Galveston where he was met by his older brother Robert, who had emigrated several years before and settled in Corpus Christi. Robert gave Hugo a job at his general store, Ritter’s Racket Store, on Mesquite Street and soon made him his partner.

[spacer height=”20px”]

Robert and Armin Ritter, brother and nephew to George Hugo Ritter (Photo courtesy of Harriet Tillman, family archives)

[spacer height=”20px”]

The brothers had a falling out over the business, which resulted in Hugo venturing out on his own to become a farmer. His daughter, Marie Josephine Ritter Werner wrote this about her father:

“Now let me tell you about Papa. I do not know if I can do justice to describing such a complex personality. At times his severity was almost frightening, and then again there would be an almost tenderness as he reached out for the good things in his wonderful America. His avid taste for reading built for him a library of history, the classics, medical books, and those on agriculture and animal husbandry. The Rural New Yorker, his favorite newspaper, taught him much about the United States farming, dairy farming, and current events. His life was almost a paradox: a city boy immigrant to become a farmer in America, overcoming the language barrier to speak, read and write English fluently. Yet he seemed to strive for something better in life. His perfectionist attitude that things must be done the right way made him appear a severe task master.” (Note: Many of these books are in the possession of Butch Roper who saved them from the old Ritter house before it burned.)

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

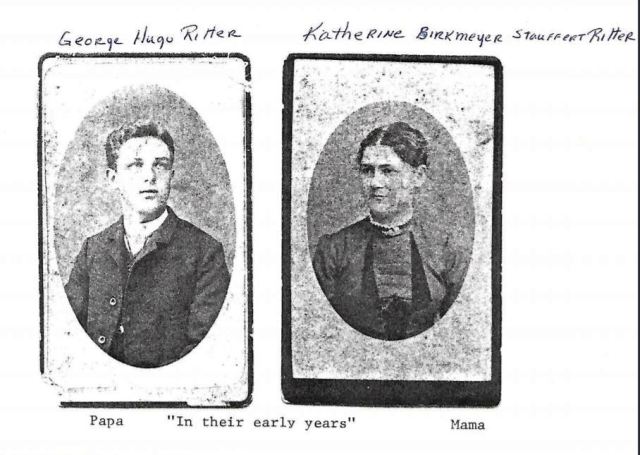

About the time of the falling out between the brothers, Hugo met Katherine Birkmeyer Staufert, also a German immigrant, through mutual German-speaking families. Katherine’s first husband, Jacob Staufert (whom she married March 16, 1887) was a sheep rancher in the area near Alice, Texas, in what was then called Collins, Texas. On January 19, 1888, Staufert took several horses into town to sell but was shot and killed on his way home for the money he had in his bag. Katherine was left a widow with a little girl, Katherine “Katie” Marie, whom Hugo gave the name Ritter and raised as his own. According to an affidavit signed by Katherine Ritter on February 17, 1925, she and Hugo married on May 28, 1889. Born unto them were eight children: Arthur Hugo (Feb. 6, 1891), Clara Ellen (May 15, 1892), Erich George (Aug. 18, 1893), Barbara Millie (Oct. 18, 1896), Anna Edith (Jan. 28, 1899), Johanna Alicia (May 16, 1901), Karl Robert Bernard (Jan. 8, 1903), and Marie Josephine (Mar. 15, 1907).

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

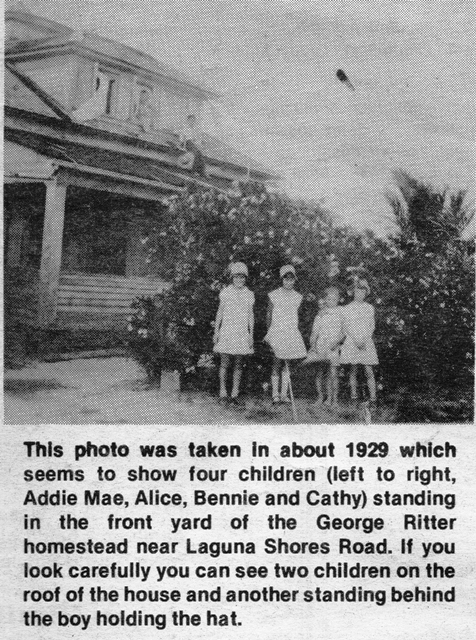

At first, the Ritters established and worked a farm near Ocean Drive just outside Corpus Christi. In 1890 during the Ropes Boom, they purchased land for about $8.00 an acre at the “grass place” which is within a few hundred yards of what is now the south gate of Naval Air Station Corpus Christi near Flour Bluff Point. They raised cows, hogs, chickens, vegetables, cotton, and corn. They were truck farmers working a 40-acre farm and delivering produce twice a week by horse-drawn carriage to Corpus Christi to sell. Three weeks after the birth of Karl Bernard (Ben), they moved to a new location on the Encinal Peninsula, an area called Flour Bluff.

[spacer height=”20px”]

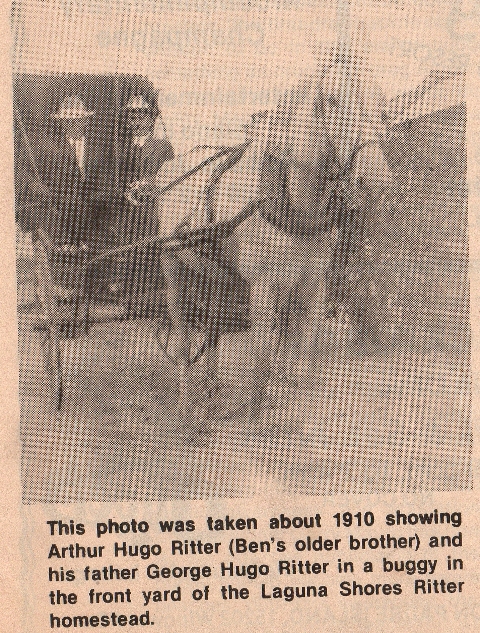

According to an interview with Ben in the Flour Bluff Sun in 1987, the new homestead was “quite close to the Laguna Madre. At that time Laguna Shores Road was only a sandy trail. Hugo bought an unfinished, large frame house next to a large pond from Mrs. Shade. It sat on 214 acres, of which 100 were farmed. In addition to finishing the lower floors of the house and running the farm, Hugo Ritter landed a contract for the construction of some Flour Bluff roads to be built of clay and sand.” Hugo was known to be a hard-working, well-read man of many talents, something that would lead him to take on many different roles in the Flour Bluff community.

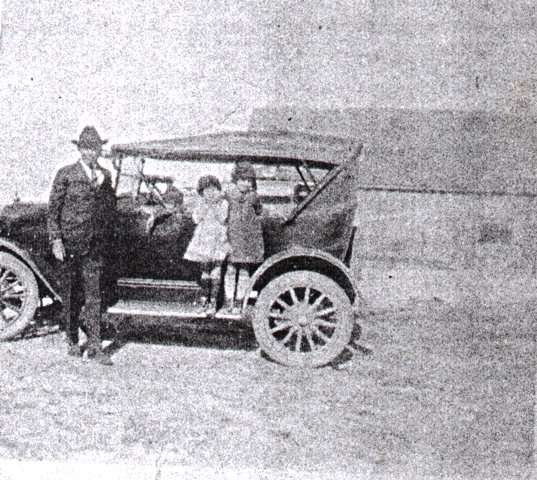

Hugo’s farm later became known as the Brighton Beach Farms Dairy. He sold directly to the customer, which brought him a greater profit. Such a business method required that the family take on the job of deliveries. His oldest son, Arthur, handled the route with butter, milk, and cream, making his deliveries in a horse-drawn wagon. The dairy business required a way to keep the products cold at the dairy and while en route. Arthur also had the job of driving the team to Corpus Christi twice each week to pick up blocks of ice. The Ritters had a wet cloth cooler at the farm where the ice was surrounded by wet cloths to keep the temperature down. In 1914, the Ritter family acquired something that made delivery much faster and easier; they bought a car. The Flour Bluff community had a Model-T Ford just six years after they rolled off the assembly line in Detroit. During World War I, Hugo supplied dairy products to the men stationed at Camp Scurry, which was located where Spohn Hospital and the Del Mar neighborhood are today.

[spacer height=”20px”]

George Hugo Ritter with Addie and Alice Ritter in his new Model T, 1914 (Photo courtesy of Kathy Orrell)

[spacer height=”20px”]

It was during this time that Hugo Ritter received a contract to open a U.S. post office in Brighton. According to a 1997 book entitled Handling the Mails at Corpus Christi by Rex H. Stever, Ella Barnes, daughter of Clarence Barnes, the first postmaster, said that her father wanted to name the post office Flour Bluff, but the Post Office Department told him that it had to be a one-word name. Barnes chose Brighton after his hometown, Brighton, Tennessee. Clarence Barnes was appointed on April 27, 1893, as the first postmaster of Brighton. George Hugo Ritter was appointed postmaster on August 28, 1906, and Katheryn M. Ritter on May 13, 1914. Early post offices in small communities were generally located at the residence or business of the postmaster. So, the post office opened by Barnes was relocated when Hugo Ritter took over.

[spacer height=”20px”]

Addie and Junior Ritter with Blackie in front of the Ritter home on what is now Laguna Shores Road. (Photo courtesy of Kathy Orrell)

[spacer height=”20px”]

He turned the front hall of the Ritter home into a post office that would serve the twelve families that lived in the community. Hugo, with the help of his sons, Arthur and Ben, built a counter across the hall, added pigeon hole boxes behind it, and a glass front to enclose it. There they collected letters, sorted the mail, and sold one- and two-cent stamps to the tiny community. To receive mail from outside the Encinal Peninsula, a member of the Ritter family would meet the regular postman on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Saturdays at the Yorktown Oso Bridge (Mud Bridge). The tiny post office discontinued service on March 31, 1920.

[spacer height=”20px”]

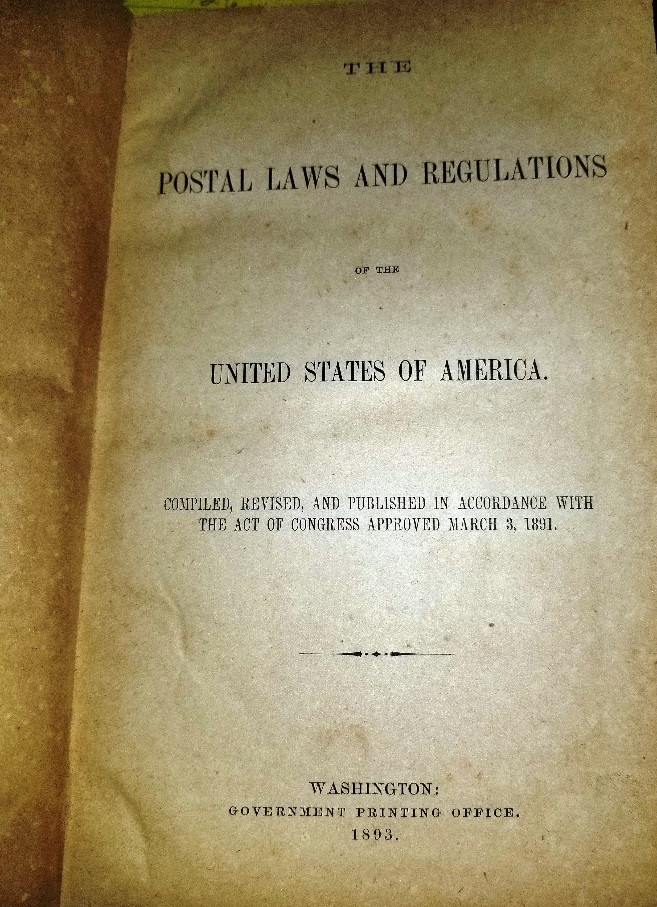

This book, presumably one used by Hugo Ritter to run the Brighton Post Office in Flour Bluff, was recovered from the Ritter house by Butch Roper.

[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

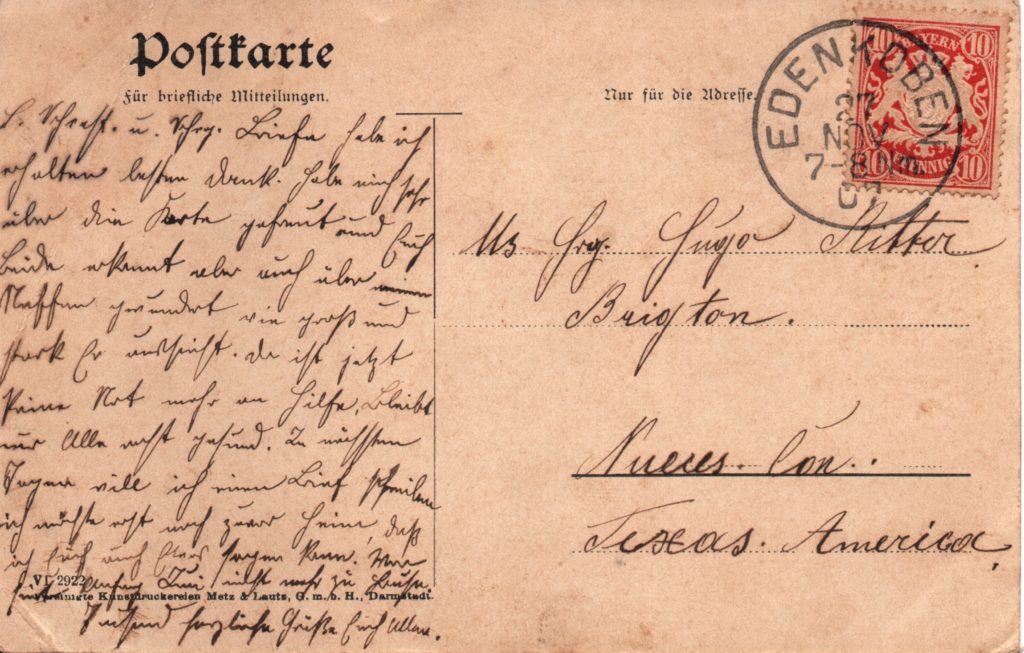

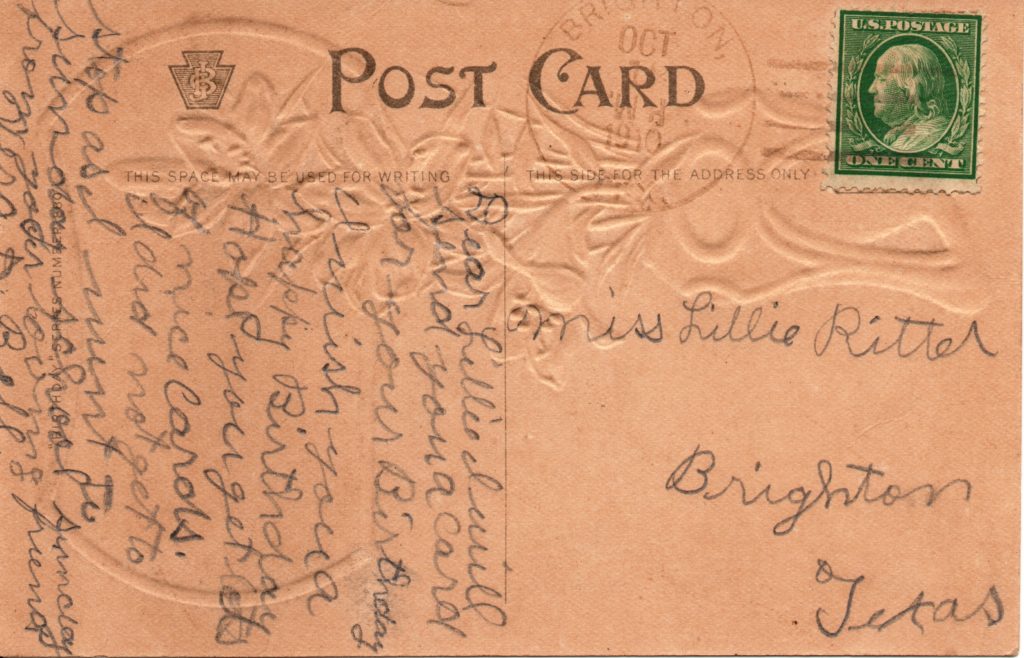

Brighton postcard, October 1910. Note the 31 mm, 4-bar black cancellation, which was used from August 1906 to March 1920. (Photo courtesy of Butch Roper)

[spacer height=”20px”]

The Ritters, along with other pioneer families of Flour Bluff, settled the Encinal Peninsula, farmed, ranched, opened businesses, started schools and gave birth to what grew into the Flour Bluff, a community which now has over 20,000 residents. Their independent, do-it-yourself spirit opened the door for others like them to shape the little town that almost was.

Sources: Flour Bluff Sun interviews with Ben Ritter, interviews conducted by Cassandra Self-Houston, personal interviews with members of the Ritter family (Butch Roper, Kathy Orrell, Deanna Myers, Cheryl Beauregard), Corpus Christi Caller-Times articles

(This article first appeared in The Paper Trail online news site on June 13, 2017 and has since been updated with additional information and photos.)