[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

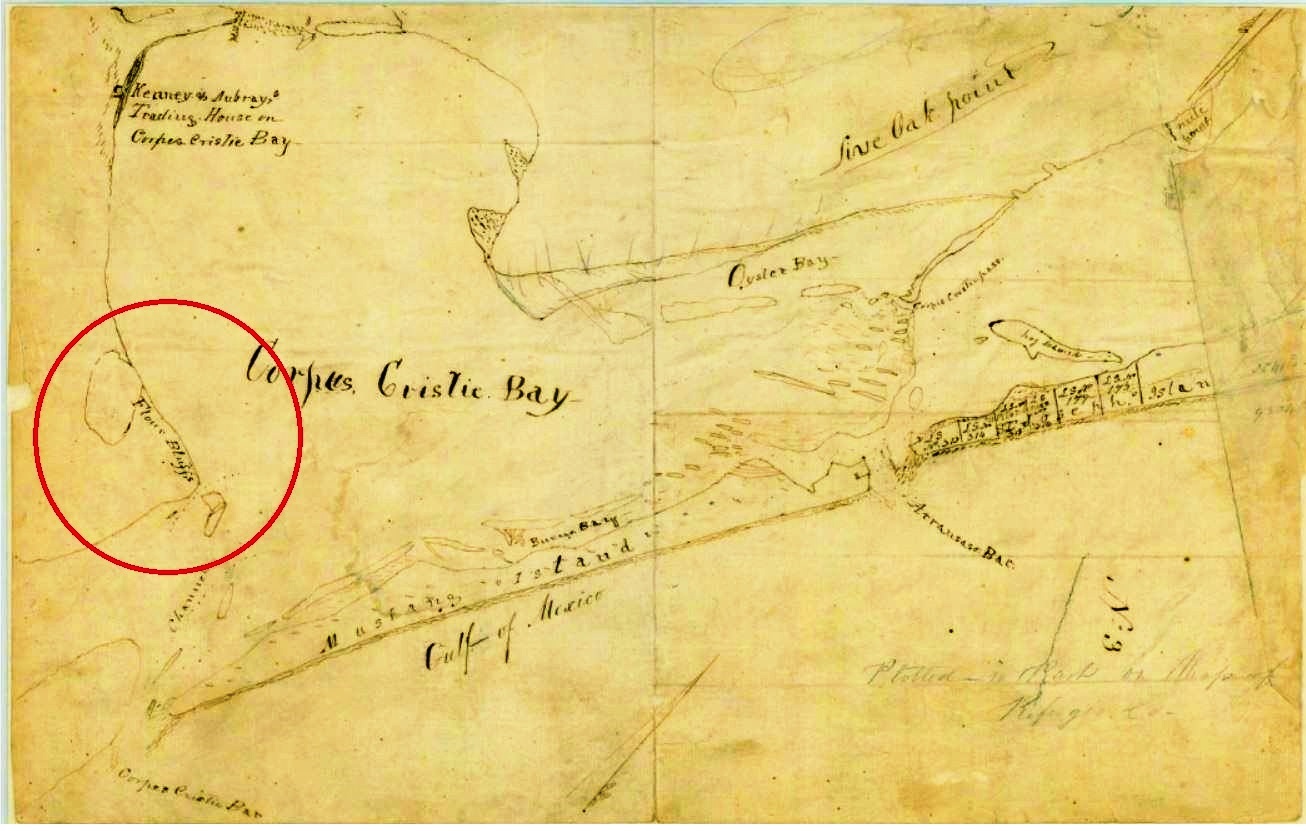

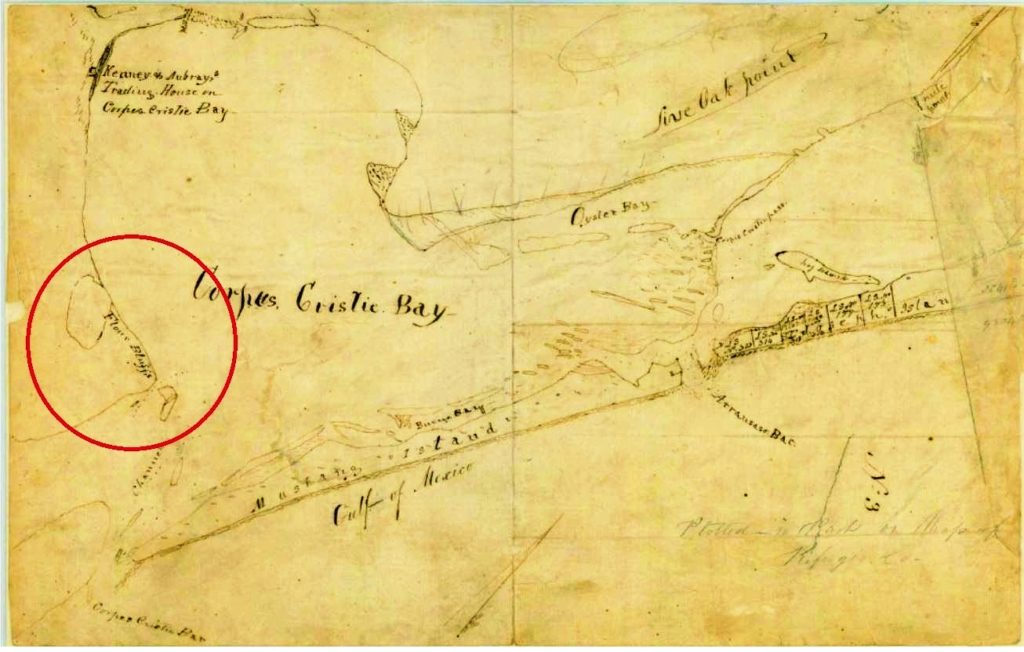

In 1839, an unnamed cartographer sketched a map of areas surrounding Aransas and Corpus Christi Bays. This map (depicted above) is in the hands of the Texas General Land Office. The area circled in red indicates the first printed use of the name Flour Bluffs, an area at the tip of what is now called the Encinal Peninsula. According to Bill Duncan in a Caller-Times article from 1963 on the subject of Flour Bluff, “In 1835, Mexico parceled out most of South Texas in grants to its citizens, a vast tract stretching from the Oso (then called El Grullo, the Grey) to Baffin and Alazan Bays” to families who probably never even saw the property because it was far off the beaten paths. The Encinal Peninsula, like the rest of South Texas, became part of the Republic of Texas in 1836. Two years later, the remoteness of this land, Duncan suggests, is what attracted smugglers to the area during the Pastry War.

According to Christopher Klein, writer for History.com, the 3-month war was actually a military conflict sparked in part by an unpaid debt to a French pastry chef.

“In the years following Mexico’s 1821 independence from Spain, rioting, looting and street fighting between government forces and rebels plagued the country and damaged property, including the ransacking of a bakery near Mexico City owned by a French-born pastry chef named Remontel. Rebuffed by the Mexican government in his attempt at compensation for the damage caused by looting Mexican officers, Remontel took his case directly to his native country and French King Louis-Philippe.

“The pastry chef found a welcome ear in Paris. The French government was already angered over unpaid Mexican debts that had been incurred during the Texas Revolution of 1836, and it demanded compensation of 600,000 pesos, including an astronomical 60,000 pesos for Remontel’s pastry shop, which had been valued at less than 1,000 pesos. When the Mexican Congress rejected the ultimatum, the French navy in the spring of 1838 began a blockade of key seaports along the Gulf of Mexico from the Yucatan Peninsula to the Rio Grande. The United States, which had a contentious relationship with Mexico, sent a schooner to assist in the blockade,” Klein reports.

This action, according to Bill Duncan, made the price of many staples jump in price, including the price of wheat. “Smuggling,” writes Duncan, “became a highly profitable, though precarious occupation. Corpus Christi Bay was a natural landing spot. The new Republic of Texas, seeking French recognition, took a dim view of the smuggling and in the late summer of 1838, Texas militiamen spotted a group of Mexicans unloading cargo on the beach east of El Grullo. They approached and the Mexicans fled. The principal item left behind was 100 barrels of flour.”

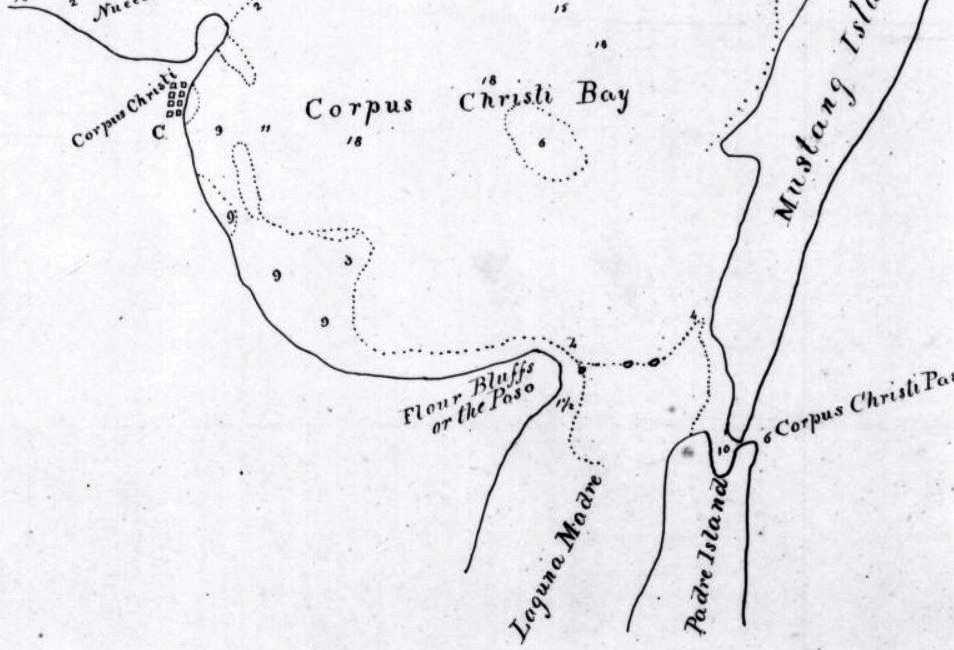

But, flour was only part of the story. It turns out that giant, white sand dunes graced the shores of Flour Bluff Point where the smuggling occurred. According to those who leveled the sandy giants in 1940 to build NAS Corpus Christi, they stood 40 feet high. Sand naturally collected in this area, according to R.A. Morton and J.G.Paine who studied the area and wrote about it in the 1984 publication, Historical Shoreline Changes in Corpus Christi, Oso, and Nueces Bays, Texas Gulf Coast. Evidently, this was apparent to the cartographers in 1845. because the Texas GLO map below shows the area with a second name, the Poso, which means “deposits” or “sediments” in English. This sandy peninsula with giant white sand dunes and 100 barrels of flour naturally led to the name Flour Bluffs, now simply referred to as Flour Bluff.

Texas GLO map showing Flour Bluffs or the Poso, 1845 (Poso translated into English means “deposits” or “sediments.”)

[spacer height=”20px”]

Santa Anna’s connection to the naming of Flour Bluff may have been ever so slight, but the story of his involvement in the Pastry War adds a little seasoning to the tale. Matthew Thornton, Texas history teacher and historian, tells of Santa Anna’s role in the Pastry Wars:

“In 1838, Santa Anna seized an opportunity for redemption while fending off a French invasion of Mexico. He once again led Mexican troops in what became another major Mexican military loss, but negotiations between France and the Mexican government eventually settled the dispute and brought end to the invasion. Though he had notched his belt with another difficult loss on the battlefield, Santa Anna was met with renewed support from the Mexican people for his will and ability to quickly rally troops and come to the defense of the country. For his troubles during the conflict, Santa Anna managed to lose his leg to cannon fire, an incident for which he chose to hold a formal burial with full military honors for his sacrificed limb. He famously donned a wooden prosthetic after the leg was successfully amputated.” (Read the full story about Santa Anna here.)

All in all, the grey, muddy waters of the Oso have long separated Flour Bluff from the rest of Corpus Christi and Texas. This geographical separation has created a difference in the land. Corpus Christi proper is black gumbo. Flour Bluff is sand. It has also created a difference in attitude, an attitude that the people of the Bluff understand and defend. Social media pages such as “I Grew Up in Flour Bluff,” “It’s a Bluff Thing,” and the like keep the current citizens attached to each other. This writer’s goal is to attach them to their history so that all can appreciate being separate but also see how they are tied to those beyond the Oso and the Laguna Madre.