[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

When Butch Roper was growing up in Flour Bluff, life was simpler in some ways and more difficult in others. He recalls what it was like playing football in what the local kids called “Grass Bur Stadium,” the field where the boys went to battle in the name of their school.

“In junior high, we had a really good team. Our coach was Johnny Johnson, and he would take us to games in his car,” said Butch. “Some of our guys were fast, real fast. When other teams would ask us why we were so fast, we’d tell them it was because we lived in grass bur country and played barefoot, so we had to run fast to keep those burs from sticking in our feet,” Butch said with a grin.

“I was the only person with shoes, but I didn’t have them long. My daddy bought me a pair, and I tried to wear them in a game, but I just could not wear those things. So, I took them off and put them on the sidelines and went back to playing barefoot. When I went back to get them after the game, somebody had stolen the damned things!”

At home, Butch was like lots of kids in the 1950s. “We didn’t have a tv. My grandparents had a Victrola that played those big heavy records, and we crank it and listen to that. The first television I remember seeing was in the Humble Camp. One or two of the families had one. It was mostly just snow and static, but we thought that was the coolest thing. There was only one station, but I don’t remember what we watched,” he said. “Back then we just listened to the radio mostly. My favorite radio show was ‘Lone Ranger.’ I listened to it all the time. It was great! There was a scary program called ‘Inner Sanctum.’ When it came on there was a creaking door, and it really scared me, but I listened to it anyway,” said Butch.

Butch’s memories of his school days took him down many paths. “I was in the first group of kids who went to HEB Camp in 1954. I was fourteen. We boys rolled a boulder down the hill that the camp wrote HEB on. I went back again in high school as a counselor. I was a fun counselor!” Butch said with a grin.

Then Butch took on a serious look. “I remember a boy named James McCutcheon coming to Flour Bluff. He came to school on a blue Navy bus, like all the kids from the base. It was 1957, and he was the first black kid in the school. That poor guy caught it. His dad was in the service, and he had to go to an all-white school with a bunch of country kids and fishermen’s kids who weren’t kind to him,” said Butch. “And, he wasn’t like the rest of us who started in first grade and went all the way to twelfth grade together. I felt bad for him.”

Racial tensions ran high across the nation in those days, and they sometimes found their way into Flour Bluff and onto the basketball court. “About a year after James came to the Bluff, we were playing West Oso, an all-black team, at our gym. Back then a tie-ball meant a jump ball. I had to jump against one of the West Oso kids, and he hit me right in the nose with his fist. It bloodied my nose, and things started getting out of hand,” said Butch. “Then, a little guy from West Oso went up for a layup, and one of the Bluff boys grabbed him and rammed him right into the stage. The ref called the game over and sent everybody home. It’s just the way it was then.”

Butch, like most kids, spent his days outdoors. “We didn’t have air conditioning like today. We had indoor plumbing in our new house, but baths were cold unless we heated water to pour in the tub,” said Butch. “The Ritter house had a well, and it’s still right out back. At one time there was a windmill, but it’s been gone a long time. I can still hit water about thirty feet down when I drop a line into the well, but we don’t use it anymore.”

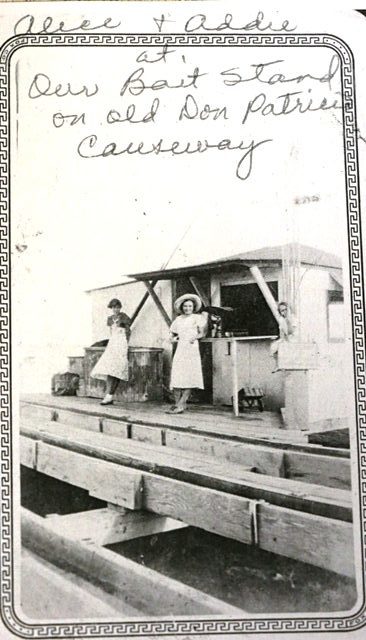

Butch talked about the old two-story house where his grandparents lived and in which they had a post office. “It wasn’t too far from where I lived. All the Ritters lived near each other on Ritter land. Uncle Ben and Aunt Opal, Fred and Ellen Gallagher, and Harry and Alice Grim lived on the land. Alice and Ellen are Ritters, and they ran the bait stand on the old Don Patricio Causeway before. Uncle Ben Ritter helped build it,” said Butch.

Ritter girls at Don Patricio Causeway bait stand (Photo from Kathy Orrell collection)

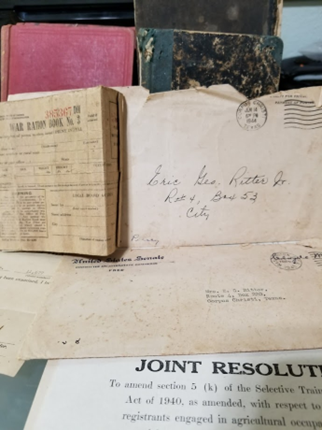

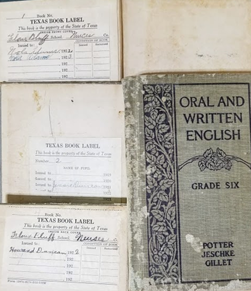

“By the time I was about 18, no one lived in the old house any longer. One night my brother-in-law and I sneaked over there and went in the old place after it was moved to the end of Don Patricio Road,” he said. “Somebody had broken into it and thrown all the old books and post cards all over, so we gathered up all we could carry and took them home. If we had not gotten what we did, we’d have nothing from the place. It wasn’t too long after that when someone got in there, started a fire, and burned it down. I wish I had gone upstairs, but I was still too scared of that ghost!”

The efforts of the two young men provided a glimpse into the past because of the books and memorabilia they saved. Butch Roper has rare post cards with the Brighton postmark, a hat brought from Prussia by his great grandfather George Hugo Ritter, dozens of English and German books from the mid-1800s, family documents regarding personal and real property, and even a few textbooks from Flour Bluff Schools. “I know some people call all this stuff junk, but I think it’s pretty neat,” said Butch.

Prussian hat worn by George Hugo Ritter, ca. 1845 (Butch Roper collection)

WWII Era documents (Butch Roper collection)

Flour Bluff Schools textbooks, early 1920s, with names of Nola Adams, Jessie Duncan, and Howard Duncan (Butch Roper collection)

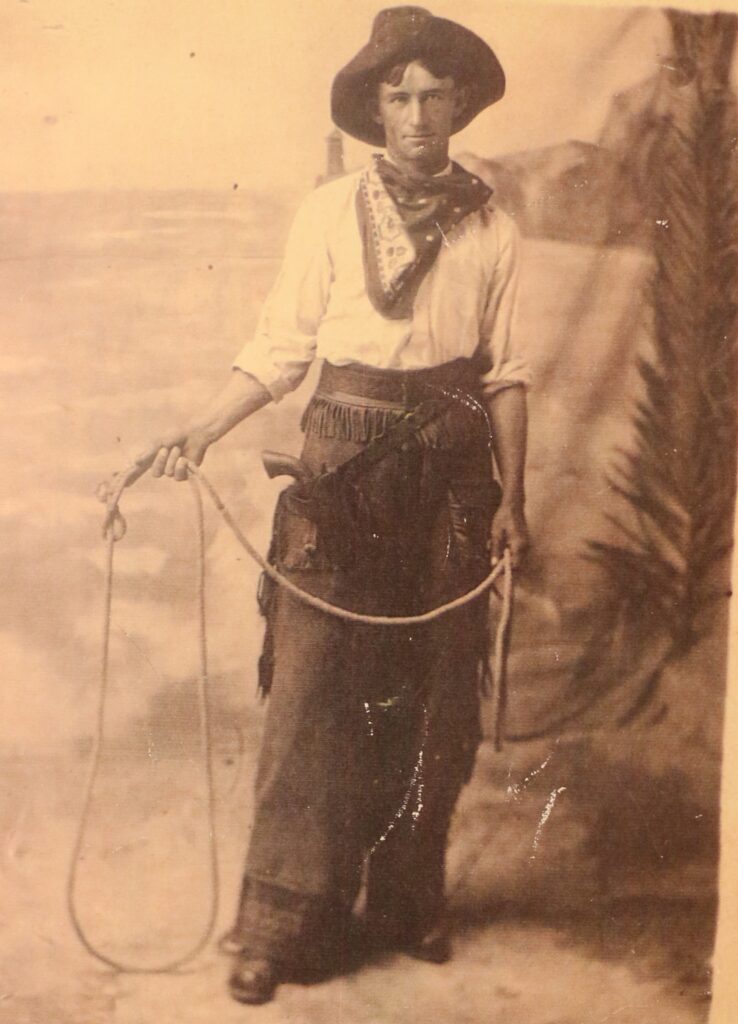

Butch has memories of the Roper side of his family, too. “They were also in the dairy business. My grandpa Simeon Ray Canfield Roper was a real cowboy. I heard that they came from somewhere in West Texas and settled in Flour Bluff near the Ritters when they all lived where the base is now,” said Butch. “At some point, he started his dairy business in Sandia, next to Knolle Farms. I loved going to that general store to get candy. At one time, Sandia – which means ‘watermelon’ – was a hopping little place. The railroad went through it, and they shipped a lot of watermelon out of there. But, he came back to Flour Bluff.”

Simeon Roper (Butch Roper collection)

When Butch graduated from Flour Bluff, he didn’t have a car. “We had a family car. I didn’t get a car until my freshman year at the University of Corpus Christi. My dad told me I could go to school or quit and go to work to get a car. I quit and got a new car,” said Butch. “I went to work at American Smelting and Refining Company on Up River Road. We made zinc blocks that were shipped out by train. I didn’t like that job because you had to mess with acid. You could shake your clothes out, and they’d just fall apart. I decided I wanted to go back to college, so I went to Del Mar for two years. All I wanted to do was play basketball. I didn’t want to study. I played city league, AAU. I even played for CP&L one year and Sun Tide another year.”

Butch remembered another job for a completely different reason. “When I was working for J. I. Haley Oil Field Services, they sent us down to Riviera. We were putting in pipeline when we heard about John F. Kennedy getting killed. Everybody was so upset.”

Butch sometimes took part time work with his brother-in-law Bob Beauregard who was married to his younger sister Cheryl. “I never commercial fished, but I fished for my brother-in-law, Bob,” said Butch. “He had a whole fleet of shrimp boats. One of them had a real tall mast on it. That’s the one we took out when we heard that they were catching a lot of shrimp in Nueces Bay. It’s really shallow and had a lot of oyster reefs.”

“On these shrimp boats, there as a small net called a try-net. It was dropped over the side to test the waters. It you pulled it up, and it had quite a few shrimp, then that’s where you’d drop the big net. It kept you from dragging around a big and wasting time when there weren’t any shrimp,” he said.

“On that day in particular, the try-net got a crab trap caught in it. I was the deckhand – as usual – so I was the one who had to untangle the net from the trap. That’s what I was doing when BOOM! Something blew by my ear and into the water, making a little atomic bomb looking cloud,” Butch said.

“I jumped and yelled at Bob, ‘What in the heck happened?’ Bob explained that he didn’t know what happened, but his marine radio was out and the mast was gone!” he said.

“Then we saw it. The mast of the boat had hit the power line that led to Portland,” said Butch. “That’s when Bob got the bright idea to call CP&L and demand they pay for his marine radio. So, when we got back, he got them on the phone. When he told them what happened, the guy on the other end told him that they had been looking for the guy who knocked out all the power in Portland. That’s when Bob hung up.”

“It all happened so fast that we never got the chance to be scared, but looking back, we realized we were lucky to be alive. All that electricity went down into the motor and burned everything up and then kicked the hatch up in the air. I guess the fiberglass hull saved us from being electrocuted,” said Butch. “This wasn’t long after Harry Grabowske got electrocuted pulling his boat down Laguna Shores. He touched a power line, and it killed him.”

Living in Flour Bluff has left Butch with many memories, some good, some not so good, and some just humorous. He has fond memories of going to HEB Camp in Leakey just up the road from Garner State Park where the Humble Camp families went on vacation. He is still in awe of going to Ouray, Colorado, on school buses with kids he’d spent his life with playing along the Laguna Madre and going to battle on the fields and in the gyms of South Texas. And, like so many along the Coastal Bend, he remembers the hurricanes that came to visit. “I wasn’t alive for the hurricanes of 1916, 1919, and 1933, but I remember my parents, grandparents, and great grandparents talking about them. They didn’t even name them at that time,” said Butch. “I do remember Carla in 1961, Beulah in 1967, Celia in 1970, Allen in 1980, and Harvey in 2017. And, we’ve always bounced back.”

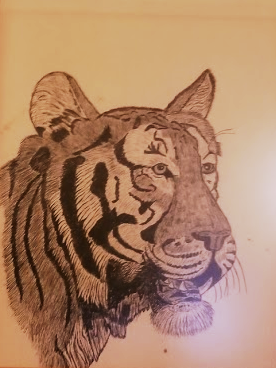

In his later years, Butch has kept the past alive through his collection of memorabilia and his telling of stories. When his body that had served him so well as a young man gave out, he took up art. Just like his people who came before him, Butch is a survivor who still finds joy in living and in spending time with his wife Marge, his family, and his friends and in giving those who know him a tale to remember.

Original drawing by Butch Roper